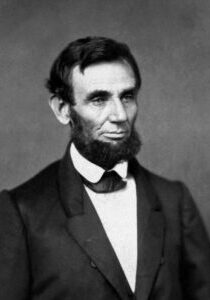

Abraham Lincoln

February 12, 1809 - April 15, 1865

16th President of the United States

16th President of the United States

From Larue County, Kentucky

Served in Illinois and Washington, DC

Affiliation: Christian

"The will of God prevails. In great contests each party claims to act in accordance with the will of God. Both may be, and one must be wrong. God can not be for and against the same thing at the same time."

Abraham Lincoln requires little introduction. Born in 1809 in Kentucky, he ascended from the obscurity of the frontier to the highest office in the land, navigating a path shaped by law, politics, and the sectional crisis of his time. As the 16th president of the United States, he bore the immense burden of leading the nation through its most intense trial, the Civil War of 1861–1865. In April of that final year, an assassin’s bullet brought his life to an abrupt and tragic end. Yet his legacy endured, venerated by many and scrutinized by others. Among the many dimensions of Lincoln’s character that invite historical debate, his faith remains one of the most elusive. While some argue he was a skeptic throughout much of his life, others contend that the weight of war and the moral gravity of emancipation deepened his belief in divine providence.

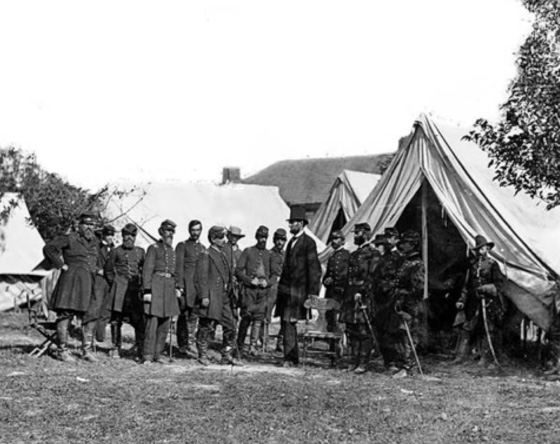

Lincoln’s political rise was forged in the rough-and-tumble world of frontier politics, where the stump speech reigned supreme. His early career in Illinois was marked by a homespun eloquence that blended wit, logic, and moral suasion. During these years, as the nation expanded westward, fierce debates emerged over whether new states would allow slavery—an issue that would come to define Lincoln’s political trajectory. Initially a devoted Whig, he championed Henry Clay’s vision of internal improvements and economic modernization. In these early years, Lincoln was not an avowed abolitionist, though he opposed slavery as a moral and political wrong. Only in the late 1850s, with the collapse of the Whigs and the rise of the Republican Party, did he take a firm stance against the expansion of slavery. His election in 1860, on a platform that rejected its spread, triggered secession and, soon after, civil war.

Though he never formally joined a church, Lincoln was profoundly influenced by religious ideas, particularly in the later years of his life. He was a lifelong reader of the Bible, and his speeches, especially those delivered during the war, are steeped in its language and imagery. His stepmother, Sarah Bush Lincoln, recalled how as a boy, he would read the Bible alongside other books of interest. His gift of oratory was evident in the way that young Lincoln would repeat sermons, almost word for word, on the stumps outside their home. While no definitive primary sources identify him as a confessing Christian in the conventional sense, his public statements often acknowledged divine sovereignty.

His Second Inaugural Address, delivered in March 1865, stands as one of the most theologically resonant speeches in American history. In it, Lincoln grappled with the moral dimensions of the war, suggesting that the conflict was not merely a national tragedy but a form of divine judgment. “The Almighty has His own purposes,” he declared, invoking the biblical notion that nations, like individuals, are subject to moral reckoning. He continued with striking force:

“Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said, ‘The judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’”

With these words, Lincoln framed the war not merely as a contest of arms but as a reckoning for the nation’s original sin of slavery.

Did Lincoln believe in a personal God? His writings suggest that he did, though his faith was unconventional. He once advised a friend, “Take all of this book upon reason that you can, and the balance on faith, and you will live and die a happier man.” While he rejected strict denominationalism and never professed adherence to Christian orthodoxy, he believed in moral truth, divine justice, and history as an unfolding of a higher design. “I am nothing, but truth is everything,” he once remarked.

Lincoln’s evolving faith was not merely a matter of personal conviction but an essential element of his leadership. The immense suffering of the Civil War weighed heavily upon him, and as the conflict deepened, so too did his reflections on divine will and national purpose. He did not invoke God casually, nor did he claim to comprehend providence with certainty. Instead, he saw the war as a trial whose meaning could only be discerned with humility. “The will of God prevails,” he wrote in 1862. “In great contests each party claims to act in accordance with the will of God. Both may be, and one must be, wrong.”

Lincoln’s profound moral struggle is evident in his private writings as well. In the wake of the staggering Union losses at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, he drafted what has come to be known as the “Meditation on the Divine Will.” In it, he speculated that the war continued because God willed it so, as part of a design beyond human understanding. This introspective approach shaped his decisions, particularly on emancipation. By 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation had transformed the war into not only a struggle for national survival but for moral justice.

By the war’s final year, Lincoln had become more religious in his understanding and expression of the war’s purpose. Yet his faith remained marked by a characteristic humility which acknowledged that human understanding of God’s purposes was, at best, incomplete. In this, as in so much else, Lincoln embodied a rare blend of pragmatism and moral vision.

Lincoln’s religious views defy simple categorization. He was neither an orthodox Christian nor a deist in the mold of the Founders. Instead, his faith, like his presidency, was shaped by the weight of events. The agony of war and the burden of leadership deepened his conviction that God’s purposes were at work in the unfolding struggle. His was the faith of a frontier politician, tempered by personal loss, sharpened by the demands of governance, and ultimately defined by the great moral crisis of his time. Historians continue to debate the nuances of Lincoln’s spirituality, yet what remains clear is that, in the darkest hour of the republic, he called upon the language of faith to give meaning to a conflict whose sacrifices defied comprehension.

For further reading:

1. Guelzo, Allen C. Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1999.

2. Havers, Grant N. Lincoln and the Politics of Christian Love. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2009.

3. Szasz, Ferenc Morton, and Margaret Connell Szasz. Lincoln and Religion. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2014.