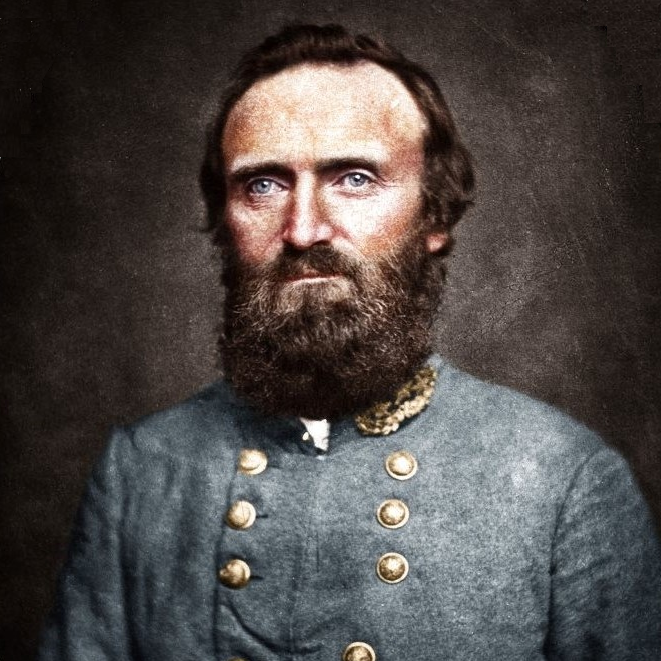

Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson

January 21, 1824 - May 10, 1863

Confederate General during the American Civil War

Confederate General during the American Civil War

From Clarksburg, Virginia

Served in Southern United States

Affiliation: Presbyterian

“My religious beliefs teach me to feel as safe in battle as in bed. God has fixed the time of my death. I do not concern myself with that, but to be always ready whenever it may overtake me. That is the way all men should live, and all men would be equally brave.”

“I have so fixed the habit in my own mind that I never raise a glass of water to my lips without a moment's asking of God's blessing. I never seal a letter without putting a word of prayer under the seal. I never take a letter from the post without a brief sending of my thoughts heavenward. I never change classes in the section room without a minute's petition on the cadets who go out and those who come in.”

Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson stands as one of the most enigmatic figures of the American Civil War, a man whose legend looms as large as the battles he fought. A proud Virginian, Jackson’s tactical brilliance was unparalleled on the field, yet he was also a man of deep conviction, his unwavering faith as central to his identity as his martial prowess. His contemporaries knew him as a soldier who fought with the certainty of divine will behind him, a belief that shaped not only his battlefield decisions but also his view of life and death itself.

Before secession, Jackson served in the United States Army and distinguished himself in the Mexican-American War. Later, as a professor at the Virginia Military Institute, he was known for his stern demeanor and unyielding discipline. Yet it was the Civil War that would immortalize him. At the First Battle of Manassas in 1861, Jackson’s brigade held firm against Union assaults, prompting General Barnard Bee to exclaim, “There is Jackson standing like a stone wall! Rally behind the Virginians!” The name stuck, and the legend of “Stonewall” Jackson was born.

Faith, however, was as integral to Jackson’s character as his reputation on the battlefield. He was a devoted Presbyterian, earning him the nickname “Old Blue Lights,” a reference to the intense evangelical piety associated with some ministers of the time. He viewed every aspect of life through the lens of divine providence, believing that every triumph and tragedy was part of God’s inscrutable design. “My religious belief teaches me to feel as safe in battle as in bed,” Jackson once remarked. “God has fixed the time for my death. I do not concern myself with that, but to be always ready, no matter when it may overtake me.”

His soldiers marveled at his unshakable composure under fire, interpreting it as evidence of both courage and divine favor. To Jackson, the battlefield was an extension of the Almighty’s will, a stage upon which the fate of men and nations unfolded according to a predestined plan. This belief in providence shaped his leadership, his strategies, and even his personal interactions. He often led his troops in prayer, and he sought to instill a sense of moral duty in his men, believing that they fought not just for the Confederacy, but for a cause sanctified by God.

Jackson’s unwavering faith did not preclude him from participating in the institution of slavery, a contradiction that reveals much about the complexities of his character and the era in which he lived. A slaveholder himself, Jackson saw his role as a master through a paternalistic lens, believing that he was carrying out a divine mandate by providing spiritual instruction to those he enslaved. His Sunday School for enslaved people in Lexington, Virginia, was seen by him as a mission of Christian duty.

Jackson’s military career reached its zenith in the campaigns of 1862 and early 1863. His famed Shenandoah Valley Campaign demonstrated a mastery of movement and deception that left Union forces bewildered. At Chancellorsville, he executed a daring flanking maneuver that shattered the right wing of the Union army, a victory that Robert E. Lee himself considered one of the finest moments of the war. Yet, in the confusion of battle, tragedy struck for Jackson. On the night of May 2, 1863, returning from reconnaissance, he was mistakenly shot by his own men. His left arm was amputated, and Lee, upon hearing the news, lamented, “He has lost his left arm, but I have lost my right.”

Complications from pneumonia set in, and Jackson’s condition deteriorated. On May 10, he drifted in and out of consciousness, his mind returning to the battlefield even in his final moments. “Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees,” he murmured before breathing his last. He was 39 years old.

Jackson’s death left an indelible mark on the Confederate cause. His loss was felt not just in the ranks of the army but in the imagination of a nation at war. What might have been had Jackson lived? Would the Confederate assault on Gettysburg have played out differently under his command? Would the war’s outcome have shifted? Such questions remain the province of speculation, yet they underscore the significance of Jackson’s presence, both in life and in memory.

After the war, Jackson’s legend was absorbed into the mythology of the Lost Cause, his image fashioned into that of the noble Christian warrior who fought with faith and ferocity. His life and deeds were recounted with reverence in the South, his statue erected in places of honor. Yet, as history has moved forward, so too has the evaluation of Jackson’s legacy. He was a brilliant tactician, a man of unshakable conviction, yet also a figure bound to a cause that sought to preserve an institution antithetical to the very faith he professed.

In studying Jackson, one encounters a man whose contradictions reflect those of his time—a deeply religious warrior, a commander both ruthless and revered, a believer in divine justice who upheld an unjust system. His life, like the war in which he fought, remains a subject of scrutiny, a reminder that history is rarely as simple as the legends it creates.

For further reading:

1. Hettle, Wallace. Inventing Stonewall Jackson: A Civil War Hero in History and Memory. (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2011).

2. Robertson, James. Stonewall Jackson: The Man, the Soldier, the Legend. (New York: Macmillan, 1997).