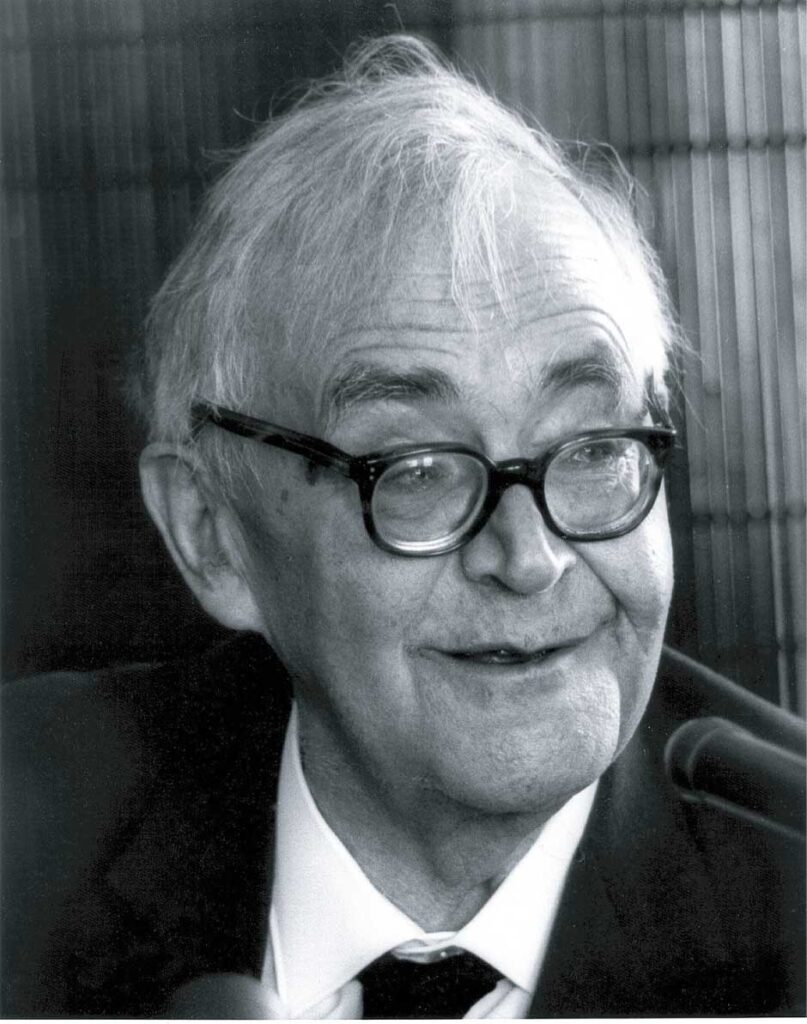

Karl Barth

May 10, 1886 - December 10, 1968

Theologian and Writer

Theologian and Writer

From Basel, Switzerland

Served in Basel, Switzerland

Affiliation: Reformed

"Jesus does not give recipes that show the way to God as other teachers of religion do. He is himself the way."

One would not put much stock in a boy who was the leader of a street gang to become a transformative theologian in adulthood. But such is the case with Karl Barth. He was not particularly fond of attending school or of behaving. He was a brawler both at school and in his neighborhood. He would eventually outgrow his “childish ways” and redirect the Church’s focus back to the unique glory of Christianity’s Founder.

Born on May 10, 1886, Barth was the eldest child of Anna and Fritz Barth, a Swiss Reformed minister. He and his four siblings were raised in Bern, Switzerland where their father was a professor of New Testament and early Church history at the University of Bern. When he reached university, Barth studied at his father’s school as well as at Berlin, Tübingen, and Marburg. He sat under the tutelage of Wilhelm Herrmann and Friedrich Schleiermacher and learned a liberal theology that emphasized the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man and not on Jesus Christ and his work on the cross.

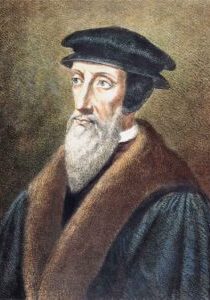

In 1909, Karl Barth moved to Geneva to be a curate, an assistant to the rector. While in his curacy, he delivered lectures in the same room where John Calvin and John Knox expounded on the Word of God. After it ended in 1911, Barth was appointed to serve a church in Safenwil, Switzerland. It was here he met his future wife, Nelly Hoffman. She was not, however, his first love. He had been dating Rösy Münger. His parents greatly disapproved and this was the catalyst for the relationship ending in May of 1910. He and Miss Hoffman met at a confirmation class he was teaching while he was an assistant pastor in Geneva. She was a talented violinist. He asked for her hand in marriage in May 1911. They wed two years later on March 27.

The ten years Barth spent in Safenwil were transformative. He arrived a liberal theologian. He left a Christo-centric theologian. Seeing the lives of blue-collar workers and their needs shifted his thinking. As well, the philosophy of the Enlightenment he learned at university eventually lost its luster. When Kaiser Wilhelm II fortified Germany with armaments and his former professors signed a letter supporting his efforts, Barth concluded liberal theology’s arguments were lean with validity. He had to “turn his back” on his instructors. His friend, Christoph Friderick Blumhardt, was instrumental in showing him Christ’s resurrection should significantly shape one’s theology. His study of St. Paul’s letter to the Romans was also a contributing factor to his change in thinking.

While in Safenwil, another shift took place in Karl Barth’s thinking. Because he believed theologically the gospel seeks to remedy social suffering, he became an advocate for the political solution to social suffering, socialism. He viewed the two as striving to fix a problem from two different, but not contradictory, perspectives. “The Red Pastor of Safenwil,” as he was called, believed “the goal of universal ‘human community of classes and peoples’ comes closer to true faith in God.” “A real socialist must be a Christian and a real Christian must be a socialist,” he said.

Eduard Thurneysen, his close friend, described Barth’s time in Safenwil thusly, “[He] did not have an easy time with his congregation, nor did his congregation have an easy time with him. … his political point of view lead to battles. That his sermons demanded of the congregation a considerable effort of understanding certainly needs no special mention. He himself found it painful that he was unable to be ‘the pastor who pleases people.’ . . . Yet it can be said that he was able to gather about him a faithful ‘little flock’ of folk who even now cannot forget their pastor of those days.”

During his time in Safenwil, Barth and Thurneysen sharpened one another’s hearts with a renewed interest in studying the Bible since Barth’s former teachers’ theology proved unsatisfying. Barth, specifically, saw the beauty of the risen Christ speaking to people through the biblical text. His heart was greatly impacted by the reality God became a man and personally revealed the Truth of the God to mankind. The discussions the two men enjoyed about the treasure of God’s revealed truth spurred Barth to write his commentary, The Epistle to the Romans. In it, he emphasized the “Godness of God … God’s absolute unique existence, power and initiative, above all in his relationship to men.” Through the work, Barth countered the 19th century liberal theology that centered on “the opinion man has of God … [not] God’s opinion of man.” Liberal theologians were incensed by Barth’s arguments and attacked him for them.

In the commentary, Karl Barth embarked on an explanation that God is unknowable without His truth graciously revealed in the biblical text. Human terms are inadequate to explain the Almighty. Barth believed paradoxical statements best captured the essence of truth (dialectical theology). In his Romans commentary, he wrote, “The veritable pinnacle of religious achievement is attained when men are thrust down into the company of those who lie in the depths,” (italics added). An excerpt from The Humanity of God also illustrates his dialectical theology: “Jesus Christ is in His one Person, as true God, man’s loyal partner, and as true man, God’s.”

The commentary on Romans was published in 1919. Barth thoroughly rewrote the book for its second edition which was published in 1922. During the period in which he wrote the new edition, his six-year-old daughter would tell people, “Daddy is writing another Romans, much better.” His second edition of The Epistle to the Romans brought him much acclaim and significant attention. Due to the commentary on Romans, the University of Göttingen appointed him a professor in 1921 despite not possessing a doctoral degree. Because of this, students were not required to attend his classes.

In total, Karl Barth and his wife had five children. Some of them would follow in his footsteps and become theologians also. Their marriage also suffered hardship. Some of the difficulty was due to what happened to them. Some was because of what Barth allowed to happen. At age 20, one of their sons, Matthias, died in a climbing accident. The trouble of Barth’s own doing pertained to his assistant, Charlotte von Kirschbaum. The two were unusually close for the presumed professional relationship they had. Due to her help with Barth’s writing projects, they formed an understandable intellectual bond, yet also an adulterous, romantic bond. Eventually, she began living with the Barths in a room off Barth’s study. The room was only accessible by going through his office.

Miss von Kirschbaum’s presence in the Barth household caused much consternation and strife to Mrs. Barth. Divorce was discussed more than once and in one instance, Mrs. Barth demanded his assistant move out or she would divorce him. She never followed through. Her children praised her years later for the excruciating circumstances she endured. “She knew indeed how indispensable Lollo von Kirschbaum’s theological assistance and unceasing participation was for carrying out this great work. That it never came in human terms to a break in our family life was magnanimous of our mother and we are thankful to her from the bottom of our hearts,” they wrote. The statement was not intended to mask the tragicness of the living situation. His children called the “three-way life … unbearable.”

His time at Göttingen was short. After four years, Barth took a position in Münster as a Professor of Dogmatics and New Testament Exegesis where he taught until 1930. During his five-year stint at Münster, he began working on his most comprehensive work, Church Dogmatics. It was not a complete work yet because he felt there was more work to be done with epistemological issues. His thinking was refined and sharpened when he moved to Bonn and interacted with Heinrich Scholz, a philosopher of science. The fruit of these discussions was Barth’s work on St. Anselm. He was at Bonn teaching systematic theology from 1930-35.

In 1932, the first part of the first volume of Church Dogmatics was published and the last part of the unfinished work was published in 1967. In total, Barth’s magnum opus contains four volumes comprised of 12 books that address the doctrines of God, God’s Word, creation, and reconciliation. Miss von Kirschbaum played a pivotal role in assisting Barth in the writing of Church Dogmatics. It is presumed her research was critical to the work. So much so, she moved into the Barth household during work on the first volume in 1929. When Alzheimer’s crippled her mental capacity, she was admitted to a nursing home in 1964. At this point, Barth’s work on Church Dogmatics ceased and an intended volume five was never written.

In 1933, German President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler chancellor of Germany. In 1934, President Hindenburg died and Hitler used the democratic system to his advantage and declared himself the leader of Germany. Hitler understood the power of religion and began coopting Christianity for his own utility. The German Evangelical Church response was split. Some supported Hitler. Some acquiesced. Some opposed. The group loyal to Hitler was called the “German Christians.”

Karl Barth fiercely opposed Nazism. In June of 1933, he wrote “Theological Existence Today!” In the pamphlet, he decried Hitler’s intent to nationalize the church and root the church in Nazi political ideology instead of in the Word of God. This point was stated again in the Barmen Declaration, which relied heavily on Barth’s position. The declaration was adopted at the Synod of Barmen in 1934. It stated in part, “Jesus Christ … is the one Word of God. … We reject the false doctrine, as though the Church could and would have to acknowledge as a source of its proclamation, apart from and beside this one Word of God, still other events and powers, figures and truths, as God’s revelation.” Barth also co-founded the “Confessing Church” which was a movement inside the German Evangelical Church. The Barmen Declaration was one of its founding documents.

In order to propagate Nazism, Hitler demanded allegiance from the university professors nationwide. Karl Barth was willing to pledge to Hitler with a qualification. “Granted, I did not refuse to give the official oath, but I stipulated an addition to the effect that I could be loyal to the Führer only within my responsibilities as an Evangelical Christian,” he said. This did not suit the Nazi authorities and Barth had to leave the country in 1935.

The authorities in Basel, Switzerland immediately appointed him Professor of Systematic Theology at the University of Basel, from where he continued to champion the causes of the Confessing Church, the Jews, and oppressed people everywhere. Barth stayed at the University of Basel until his retirement in 1962. In addition to teaching at the university, he also preached to the prisoners kept at the prison in Basel.

After World War II ended, German Christian leaders recognized their collective passivity during the rule of the Third Reich. They had not opposed Hitler with any consequence let alone vigor except regarding government intrusion into church life. Barth co-authored a document admitting as such, the Darmstadt Declaration. In the statement, the German church admitted their inaction and said they would oppose West Germany rebuilding its arsenal.

Upon his retirement from teaching, in 1962, Karl Barth visited the United States for the first time. His teaching through his books preceded him and were a continual source of influence on many American pastors’ sermons. Because of this, when he came to visit his son, Markus, and others, Time magazine recognized the occasion and placed him on its cover. He visited Chicago first where his son taught New Testament at the University of Chicago. He also visited and taught at Princeton Theological Seminary and other educational institutions. He also met with people such as Billy Graham, Martin Luther King, Jr., and President Kennedy’s staff. In light of his interest in the American Civil War, he also went to Gettysburg.

In retirement, Barth’s health began declining. He had a stroke in 1964 and was unable to speak for a half a day afterward. Barth, however, continued to write until his last day. His emphasis on the transcendence of God also lasted until the end. On the night before his death, December 9, 1968, in Basel, he spoke with his dear friend of many years, Eduard Thurneysen, over the phone. “Just don’t be so down in the mouth, now! Not ever! For things are ruled, not just in Moscow or in Washington or in Peking, but things are ruled – even here on earth—entirely from above, from heaven above,” he encouraged Thurneysen with. In spite of his marital infidelity and due to God’s unfathomable grace, Barth’s thinking was overwhelmed by a God of massive power who humbled himself to communicate Himself personally to mankind. This was the biblical truth he spent his entire life communicating in the Church, the classroom, and on the page.

Karl Barth died on December 10, 1968. He lived to be 82 years of age.

SOURCES: Princeton Theological Seminary, Women in Theology, Christian Century, Encyclopedia Britannica, Christianity Today, Musée, PostBarthian.com, and Oxford University Press.