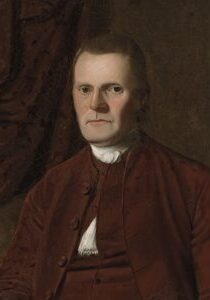

Harold J. Ockenga

June 6, 1905 - February 8, 1985

Founding President of Fuller Seminary and Gordon–Conwell Seminary

Founding President of Fuller Seminary and Gordon–Conwell Seminary

From Chicago, Illinois

Served in Boston, Massachusetts and Pasadena, California

Affiliation: Congregational

"There has evolved today a different emphasis … one that is able to say, ‘Christ is the answer. Christ is the answer to your sin problem. Christ is the answer in the biblical framework of reference because there is no other Christ. Christ is the answer when he and his teachings and biblical Christianity become translated into the framework of the social picture in which we live."

In the 1940s and ‘50s, American Christianity was in contention with itself. After the Scopes Trial in 1925, Christians had retreated from the public square. At the trial, the state prosecutor, William Jennings Bryan, was asked a series of questions about miracles in the Bible. He was peppered with questions about Jonah’s encounter with a great fish, Joshua and the sun standing still, the seven of days of creation, and more. His answers were less than convincing and substantive. Christianity began to viewed as unintellectual and unscientific. It was in this post-World War II moment that a young pastor from Boston had the vision to display the intellectual depth of the Christian faith.

Harold John Ockenga was born on June 6, 1905 to Herman and Angie Ockenga. The son of German forebearers was converted at 11 years of age, but a struggle remained in his soul. A Methodist youth leader, Alice Pfafman, noticed his discontentment and invited him to attend a youth conference in Galesburg, Illinois. During one sermon, he and other attendees were encouraged to surrender their lives to God. Harold responded by “pouring out his life” to God. At this time, he also believed God called him to be a preacher and God gave him a “second work of grace.” In Methodism, a second work of grace is being sanctified to the point of loving God and people perfectly. This work does not result in sinless perfection.

At first, young Harold did not want to tell anyone about what occurred. Eventually, he told Mrs. Pfafman. One warm February day he stopped by her house before he was to play a round of golf. He said, “Mrs. Pfafman—you are right. God is calling me to the ministry and I have decided to respond.” Upon retelling the story some time later, he remarked, “With some expression of joy, which I do not recall, she thanked the Lord and I left for the best game of golf I have ever played in winter or summer.” Mrs. Pfafman called his mom and told her the news. His mother reacted, “Thank God. I dedicated him to the ministry before he was born.”

In 1923, Harold Ockenga began his studies at the then-Methodist institution, Taylor University. He excelled in preaching while enrolled. His nickname on campus was “the gifted orator from Illinois.” He was a part of the school’s “Gospel Teams” and preached over 400 times in American churches the teams traveled to and served.

For his graduate studies, Ockenga studied at Princeton Theological Seminary. At Princeton, his mind was expanded to see and understand the intellectual depths of God’s truths. The professor who was a significant shaper of the future leader’s thought processing was J. Gresham Machen. He was one of the key defenders of fundamentalism against modernism. The battle between the two philosophies had been raging for almost a decade before Ockenga enrolled. Overall, modernists viewed the Christian faith through a lens skewed by the Enlightenment and 19th century liberal theology. The fundamentalists held to Christian orthodoxy.

One of the key issues of the time was the inerrancy of scripture. This doctrine was being challenged by Harry Emerson Fosdick, a New York pastor, and others who viewed the holy scriptures in a modern manner. Their view was heavily influenced by Darwin’s theory of evolution and other advances in science. “It is primarily an adaptation, an adjustment, an accommodation of the Christian faith to contemporary scientific thinking,” Fosdick said in a sermon.

The modernists eventually gained control of Princeton. This led Drs. Machen, Robert Dick Wilson, and Cornelius Van Til to leave the seminary and found Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia in 1929. Ockenga had a front row seat to the major doctrinal divide that had been growing in American Christianity and had now become a chasm. He witnessed men with Christ-like boldness stand their ground without regard for their reputations among theiracademic peers.

After his studies were complete at Westminster, Harold Ockenga served as a pastor for a church in New Jersey for a short time. Then, he moved to Pittsburgh and was the pastor at the First Presbyterian Church of Pittsburgh in January 1931. He moved over to Point Breeze Presbyterian Church in May of the same year. Dr. Machen spoke at both of Rev. Ockenga’s installation services. While in Pittsburgh, he studied at the University of Pittsburgh and received a PhD in philosophy. He also met his wife, Audrey Williamson, during this time. They wed in 1935. The next year, they moved to Boston where Dr. Ockenga pastored the historic Park Street Church for 32 years.

His service in the pulpit at Park Street was characterized with eloquence and dynamism. He utilized a range of disciplines in his preaching in order to exposit each biblical text and elaborate on its import for the time at hand. Not only theology, but also cultural commentary, church history, and philosophy were part of his sermonic arsenal. By using these various tools, he exposed the lies in false doctrines and the pitfalls of political ideologies stunting human flourishing.

In light of the American Church’s retreat from culture, Rev. Ockenga desired to educate laypeople so they could engage with culture and impact it biblically. So he established the Boston School of the Bible which offered classes in evangelism, doctrine, missions, and apologetics. Hundreds of people enrolled even those from modernist churches. But the impact he desired never took place.

At the same, Harold Ockenga was also concerned with the spiritual malaise that had fallen over Boston. Since he had begun leading Park Street, he yearned for a revival. He said, “I am talking now about a heaven-sent, Holy Ghost revival, given in the sovereignty of God with no human explanation for it whatsoever.” With much prayer and much work, he held revival services and invited well-known evangelists to preach to the congregants of Park Street. Revival, however, did not come … until 1950.

In 1949, evangelist Billy Graham had just held a crusade in Los Angeles for eight weeks with an attendance of 350,000. This was his largest to date in his early evangelistic ministry. As Rev. Ockenga was spearheading a New Year’s Eve youth rally in the 6,000 seat Mechanics Hall, a member of his congregation, Allan Emery Jr., suggested inviting the young evangelist. The Boston crusade was to begin on December 31st, but it actually began on December 30th as Graham and his team sensed a “warm moving of the Holy Spirit.” It was also to be ten days of evangelizing, but it was extended to 18 days due to overwhelming interest. Also, most of the meetings took place at Park Street Church, but thousands of people were being turned away for lack of seats. Larger venues were booked for the latter portion of the crusade with the final meeting being held at Boston Garden. At capacity, 25,000 people attended and 10,000 were turned away.

Rev. Ockenga had told the audience at the outset of the crusade that they had arrived at a “turning point” in Christian history. “Millions of Americans believe an old-fashioned spiritual revival could preserve our God-given freedoms and way of life,” he said. In light of His gospel being preached, God brought 3,000 people to Himself. The Boston Herald reported New England was “on the verge of a great sweeping revival such as it has not seen since the days of Jonathan Edwards.” Graham would return to New England later for a 16 city series of meetings.

Harold Ockenga rejoiced over the Lord’s work. “I believe that 1950 will go down into history as the year of the heaven-sent revival,” Ockenga later reflected. The Boston meetings also greatly impacted Billy Graham. In his autobiography, he wrote, “Almost a half century later, it is impossible to re-create the nonstop activity and excitement that engulfed us during those months following our meetings in Los Angeles and Boston. At times I felt almost as if we were standing in the path of a roaring avalanche or a strong riptide, and all we could do was hold on and trust God to help us.”

The Boston crusade brought together two men who would shape the contours of American Christianity in the form of New Evangelicalism for the reminder of the 20th century. The movement was the eventual result of the conflict between Protestant Fundamentalists and Protestant Modernists. As stated earlier, biblical inerrancy was one point of contention. The other doctrines of the faith impacted by advances in science and modern thought were Christ’s deity, the virgin birth of Christ, the atonement, the bodily resurrection of Christ, the second advent of Christ, among others. Rev. Ockenga and the New Evangelicals believed the tenets of orthodox Christianity, but believed Christians should not isolate themselves from society and cultural institutions. As well, the Fundamentalists focused solely on the spiritual health of people. Whereas, Ockenga wanted to live as Jesus did meeting both physical and spiritual needs.

In light of this desire, Rev. Ockenga founded War Relief and the War Relief Commission in 1944 near the end of the Second World War. War Relief would later become World Relief. By meeting the physical needs of those impacted by the war, he was differentiating himself from the Fundamentalists. He also wished to correct the perception that Christians were anti-cultural and anti-intellectual. He desired to build a network of orthodox Christians that engaged society in a deep, honest, and intellectual manner. With the help of J. Elwin Wright of New England Fellowship, they founded the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE).

On April 7, 1942, Harold Ockenga addressed 150 delegates in St. Louis to launch the nascent organization. “Gentlemen, we are gathered here today to consider momentous questions [and to] arrive at decisions that will affect the whole future course of evangelical Christianity in America. Evangelical Christianity has suffered nothing but a series of defeats for decades. The terrible octopus of liberalism [had] spread itself throughout our Protestant Church, dominating innumerable organizations, pulpits, and publications, as well as seminaries and other schools,” Ockenga declared. He also spoke of the “poison of materialism” and the “floods of iniquity” in the country. He served as president from 1942 until 1944.

Overall, Rev. Ockenga wanted Christians to be united on four key areas: the Bible as the authority, conversion as the common experience, the conviction salvation was accomplished only by Christ’s death, and a shared calling to evangelize the nations. In the early years of the NAE, he traveled extensively to promote the organization’s goals. He was involved beyond his presidency until his death in 1985.

In his address to the NAE delegates, Rev. Ockenga pinpointed, in his mind, the deficiency for American Christians was a lack of intellectual depth. He observed the inability of Christians to apply scriptural principles combine with scholarly knowledge to the most significant issues of the day. “Where are the political leaders in high places of our nation,” he asked, “with a knowledge of and regard to the principles of the Word of God? The need is even more evident in the business world.”

In 1956, Harold Ockenga and Carl F.H. Henry (founding editor) joined Billy Graham, along with others, in founding Christianity Today. The magazine was Rev. Graham’s vision and its mission, according to him, was to restore “intellectual respectability and spiritual impact to evangelical Christianity.” Ockenga also helped fundraise for the publication and secured significant support from Park Street Church. He served as chairman of the board for 31 years.

Rev. Ockenga also helped found another institutional cornerstone of New Evangelicalism with Carl Henry, Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, California. Other key founders include the seminary’s namesake Charles Fuller, a radio evangelist, and Harold Lindsell, a Christian author and scholar. Again, the focus was penetrating secular society. This time the mechanism was the classroom. The group’s aim was to build an evangelical Caltech with robust scholarship and Christian orthodoxy. The seminary’s graduates would fan across the country with the skill to present the flaws of the modern, scientific worldview and reveal the shallowness of liberal theology. In addition, graduates would catalyze a movement of evangelism and global missions. In September 1947, classes began and Ockenga was appointed president. He served in absentia from 1947 to 1954 and for another term, 1960-1963.

Over the roughly final third of his life, Harold Ockenga experienced disappointment as the National Association of Evangelicals and Fuller Seminary failed to fully achieve the potential of their impact on culture. Christians who had been at odds with each other in the early part of the 20th century never reconciled. Fundamentalists became fully insular and refused to partner with the new evangelicals. Ockenga experienced this firsthand with his good friend and former Westminster classmate, Carl McIntire. He felt Ockenga had not separated enough from mainline denominations. Rev. McIntire founded a rival organization, American Council of Christian Churches. Their friendship suffered greatly and the two never fully reconciled. It was a blow to Ockenga for the remainder of his life.

Also, evangelicals turned inward. Instead of using their networks and organizational power for the transformation of culture, they poured their efforts into building and expanding Christian organizations. At Fuller Theological Seminary, the rifts present in the “fields of harvest” were also present in the “ivory tower.” The school’s theological structure shifted toward progressivism after Rev. Ockenga left his post of president in absentia.

In 1969, upon retiring from pastoring Park Street Church, Harold Ockenga was set to lead Gordon College and Divinity School, which was located northeast of Boston. In the same area, Conwell School of Theology had recently become independent of Temple University in Philadelphia. Dr. Ockenga, Billy Graham, and philanthropist J. Howard Pew drew up a plan to create an East Coast seminary in the vein of Fuller Seminary. The merger occurred in 1969 and Ockenga served as president from 1970-79.

Dr. Ockenga also helped lead other organizations: American Board of the World Evangelical Fellowship (president), Christian Freedom Foundation (director), Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (board member), Evangelical Book Club (editor), and the National Association of Evangelicals’ International Commission (chair). One might wonder how he was able to manage all of his responsibilities. He explained a prayer list helped him keep track of what needed an answer, what was resolved, and what was ongoing. He kept such a list for 41 years and placed responsibilities and projects on it.

In addition, Dr. Ockenga read a book a week and authored a dozen books. They ranged from books explaining biblical themes to Bible commentaries. With all his accomplishments and duties, he could have possessed a spirit of self-important. His friend, Harold Lindsell, said he was “warm and tenderhearted.” Many regarded Dr. Ockenga with great esteem “for he seemed to reign from Olympian heights. But once his reserve was penetrated, one found him to be a congenial, down-to-earth,” Lindsell said.

Early in 1985, this man with Herculean perseverance in serving his King understood his time was coming to an end. Cancer was ending his life. He asked the elders of Park Street Church to visit him at his home and pray for him. They anointed him with oil and strove to encourage him. They spoke of his many accomplishments and the millions of people he had served. None of this seemed to change his disposition. His heart was touched, however, when one elder said, “Well, Harold, I suggest that when you see the Master, just say, ‘God be merciful to me a sinner.’” Ockenga’s cheeks became wet with tears.

Harold Ockenga died on February 8, 1985. At his funeral service, Billy Graham characterized his friend with the kindest words. “He was a giant among giants. Nobody outside of my family influenced me more than he did. I never made a major decision without first calling and asking his advice and counsel. I thank God for his friendship and his life,” Rev. Graham said.

In his pursuit to be like his Lord, Rev. Ockenga cared for the destitute, brought the message of salvation to many, and fought for the faith and fidelity to it. He also, however, experienced great disappointment during his life as Christians failed to coalesce around his goal of heightening the intellect of the American church. Even though, he is considered a “giant” of the faith, he was not immune from difficulty. He displayed great faithfulness in the midst of both blessings and setbacks.

Harold John Ockenga lived to be 79 years of age.

SOURCES: Christian History Institute, Christianity Today, Christianity Today 2, and Desiring God