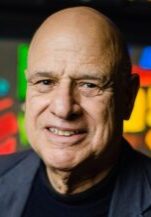

Harry Emerson Fosdick

May 24, 1878 - October 5, 1969

Pastor and Theologian

Pastor and Theologian

From Buffalo, New York

Served in Bronxville, New York

Affiliation: Baptist and Presbyterian

"Some Christians carry their religion on their backs. It is a packet of beliefs and practices which they must bear. At times it grows heavy and they would willingly lay it down, but that would mean a break with old traditions, so they shoulder it again. But real Christians do not carry their religion, their religion carries them. It is not weight, it is wings. It lifts them up, it sees them over hard places. It makes the universe seem friendly, life purposeful, hope real, sacrifice worthwhile. It sets them free from fear, futility, discouragement, and sin — the great enslaver of men's souls. You can know a real Christian when you see him, by his buoyancy."

Harry Emerson Fosdick was one of the most influential Protestant voices of 20th-century America. A pastor, writer, and public intellectual, he became the face of liberal Protestantism during the nation’s great theological divide known as the Fundamentalist-Modernist Controversy. With clarity, conviction, and a deep belief in both faith and progress, Fosdick challenged the rigidity of his age and sought to make Christianity relevant in a world transformed by science, war, and social change.

Born in 1878 in Buffalo, New York, Fosdick grew up in a Baptist home steeped in the values of faith and education. He attended Colgate University and later Union Theological Seminary, an institution known for its progressive theology and commitment to social issues. It was at Union that Fosdick absorbed many of the ideas that would come to define his ministry, chief among them the conviction that religion must adapt to the insights of modern life rather than remain bound to ancient formulations.

In the years before World War I, Fosdick served in churches across New Jersey and Manhattan, quickly building a reputation as a gifted preacher. His sermons were thoughtful, literary, and intellectually engaging. He did not thunder from the pulpit but reasoned, inviting listeners into reflection. When the First World War broke out, Fosdick joined the U.S. Army as a chaplain and served with American forces in France. His idealism about the war soon gave way to disillusionment, and he later referred to his enlistment as the act of a “fool.” The experience deepened his commitment to pacifism and to a Christianity grounded in compassion and realism.

After the war, Fosdick accepted a call to First Presbyterian Church in Manhattan, even though he remained a Baptist by denomination. The congregation, like much of the country, was caught in the midst of competing religious visions between the doctrinal certainty of fundamentalism and the exploratory openness of modern theology. It was in this climate that Fosdick delivered his most famous sermon, “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” on May 21, 1922.

In that sermon, Fosdick asked whether the church would become a narrow enclave for those who accepted every point of fundamentalist theology, or whether it would remain broad enough for those who believed in evolution, questioned the literal interpretation of Scripture, or viewed the virgin birth and Second Coming not as historical necessities but as theological symbols. “The present world situation,” he argued, “smashes the fixed, dogmatic attitude toward religion as a child smashes a toy.” He urged the church to embrace intellectual freedom, to make room for doubt, and to speak to the modern world in its own language.

The response was swift and fierce. Across the country, ministers condemned Fosdick as a dangerous liberal. The most prominent response came from Clarence E. Macartney, a Presbyterian pastor in Philadelphia and a leading fundamentalist voice. His rebuttal sermon, “Shall Unbelief Win?”, framed Fosdick as emblematic of everything that was undermining traditional faith.

The controversy between Fosdick and Macartney laid bare a deeper rift within American Protestantism. It was not simply a dispute over doctrine; it was a struggle over the future of the church. Would it cling to the creeds of the past, or would it reinterpret its faith to meet the new realities of the 20th century? For Fosdick, the answer was clear. He believed that theology must be dynamic, not static, and that the spirit of Christianity was more important than any specific formulation of belief.

The fallout from the sermon was dramatic. Under pressure from conservative forces within the Presbyterian Church, Fosdick resigned from his post in 1924. Yet the move only increased his stature. In 1925, he was invited to become the founding pastor of the newly built Riverside Church in New York City, a grand, interdenominational congregation funded by John D. Rockefeller Jr. Riverside became a model for urban, progressive Christianity which was open, ecumenical, and socially engaged.

At Riverside, Fosdick preached to thousands each week and reached many more through national radio broadcasts. He spoke out against American militarism, supported conscientious objectors during World War II, and urged the church to confront systemic injustice at home and abroad. He also became one of the early religious figures to publicly support the work of Alcoholics Anonymous, recognizing in its principles a reflection of spiritual truth.

Fosdick was a prolific author, writing more than 30 books. His works ranged from theological treatises to practical guides for personal growth. He had a gift for taking abstract religious ideas and making them accessible and helpful to ordinary people. In his writing, as in his preaching, Fosdick combined intellectual rigor with spiritual warmth.

His influence extended well beyond the church. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who called Fosdick “the greatest preacher of the century,” was shaped by his sermons and writings. Fosdick’s voice, calm and reasoned, gave strength to a generation of Christians seeking to balance faith with social progress.

Yet Fosdick was not without critics. To the fundamentalists, he was a dangerous relativist who had gutted the Christian gospel of its truth. Even some fellow liberals believed he placed too much emphasis on tolerance at the expense of clarity. But Fosdick remained convinced that the future of Christianity depended on its ability to speak to the real world, with all its doubt, complexity, and change.

Harry Emerson Fosdick retired from active ministry in 1946 but remained a public figure and advisor to many younger clergy. He died in 1969, leaving behind a legacy of faith deeply engaged with the world. His life and work represented a particular vision of American Christianity that was confident in its message, open to modern thought, and passionately committed to moral progress.

In an age of conflict, Fosdick chose dialogue. In a time of rigidity, he preached openness. His voice remains one of the clearest expressions of the liberal Protestant tradition in American history.