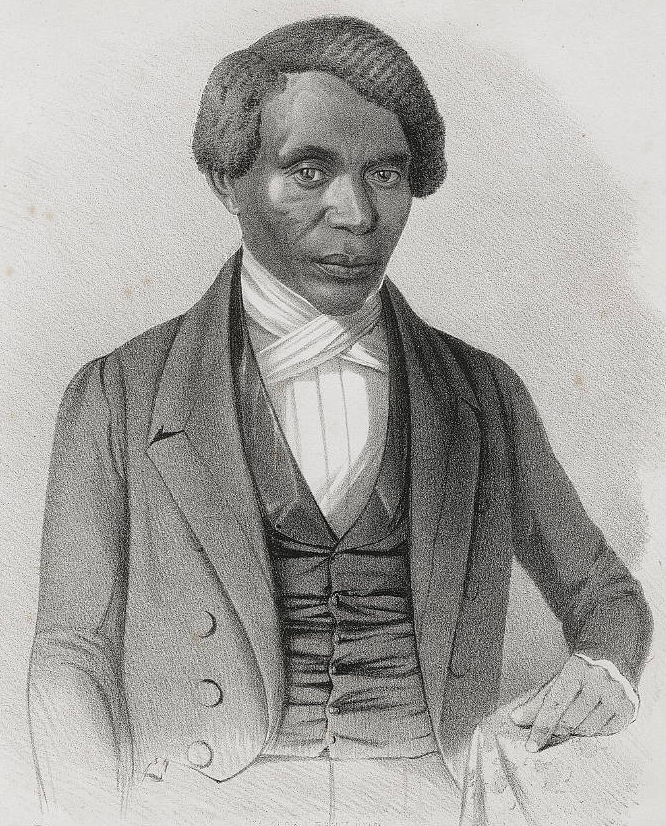

Theodore S. Wright

January 1, 1797 - January 1, 1847

Pastor and Abolitionist

Pastor and Abolitionist

From New York City, New York

Served in New York City, New York

Affiliation:

"Thanks be to God, there is a buoyant principle which elevates the poor down-trodden colored man above all this:—It is that there is society which regards man according to his worth; it is the fact, that when he looks up to Heaven he knows that God treats him like a moral agent, irrespective of caste or the circumstances in which he may be placed. Amid the embarrassments which he has to meet, and the scorn and contempt that is heaped upon him, he is cheered by the hope that he will be disenthralled, and soon, like a bird set forth from its cage, wing his flight to Jesus, where he can be happy, and look down with pity on the man who despises the poor slave for being what God made him, and who despises him because he is identified with the poor slave. Blessed be God for the principles of the Gospel. Were it not for these, and for the fact that a better day is dawning, I would not wish to live.—Blessed be God for the antislavery movement. Blessed be God there is a war waging with slavery, that the granite rock is about to be rolled from its base. But as long as the colored man is to be looked upon as an inferior caste, so long will they disregard his cries, his groans, his shrieks."

Theodore S. Wright was one of the founding members of the American Anti-Slavery Society and a towering figure in American abolitionism. Born in 1797 in Providence, Rhode Island, Wright’s life was defined by his dual commitment to faith and freedom. As an African American man in the early 19th century, his very existence was a testament to his belief in liberty, rights, education, and ultimately citizenship.

Wright’s most significant educational achievement was becoming the first African American graduate of Princeton Theological Seminary in 1828. This accomplishment was groundbreaking, not only for Wright personally but for African Americans aspiring to theological education. His time at Princeton shaped his intellectual and spiritual life, providing him with the theological training and moral conviction that would underpin his abolitionist work.

Wright’s faith was a faith that demanded action. He was a pastor at the First Colored Presbyterian Church in New York City, where he not only preached against slavery but also put his beliefs into practice. His home served as a station on the Underground Railroad, providing shelter and aid to freedom seekers escaping bondage in the American South.

Wright’s abolitionism was rooted in his understanding of Christian theology, particularly the concept of the Imago Dei, the belief that all humans are made in the image of God. This belief underpinned his insistence on the inherent dignity and worth of every person, regardless of race. It also fueled his advocacy for African American rights, including the right to self-defense. In a time when some abolitionists advocated for passive resistance, Wright insisted that Black men and women had a right to protect themselves and their communities from violence.

A powerful orator, Wright was known for his ability to articulate the moral and spiritual dimensions of the fight against slavery. He was an active member of the American Anti-Slavery Society and traveled to speak at conventions, where he called for the immediate abolition of slavery and for African American education and civic participation. Wright’s voice was one of both conviction and compassion, reflecting his deep faith and his commitment to justice. Wright and the Tappan brothers, Arthur and Lewis, were pivotal figures in the American Anti-Slavery Society, working tirelessly to advance the abolitionist cause. Arthur and Lewis Tappan, wealthy New York merchants, provided critical financial support, using their wealth to fund publications, hire lecturers, and support legal battles for enslaved individuals seeking freedom. Wright, a gifted preacher and educator, brought moral authority and leadership, becoming one of the first African American ministers to actively participate in the society. His eloquence and passion gave a powerful voice to the struggles of Black Americans, while his presence within the organization challenged its members to live up to the ideals of equality they professed. Together, Wright and the Tappans helped transform abolitionism from a scattered, often persecuted cause into a powerful, organized national movement, combining moral conviction with practical strategy.

Wright’s role in the abolitionist movement is sometimes overshadowed by more widely known figures like Frederick Douglass or William Lloyd Garrison. Yet his contributions were significant. As a Black minister advocating not only for freedom but for the full inclusion of African Americans in American life, he bridged the gap between faith and social justice in a way that was both radical and profoundly influential.

A major aspect of Wright’s abolitionist action was as a conductor on the Underground Railroad in the metropolitan hub of New York City. The Underground Railroad was a secret network of routes, safe houses, and courageous individuals who aided enslaved people escaping from bondage in the American South to freedom in the North or Canada. Operating from the late 18th century through the Civil War, it was neither underground nor a railroad but rather a decentralized, grassroots movement led by abolitionists, free Black communities, and sympathetic whites. “Conductors” like Harriet Tubman risked their lives guiding fugitives from one “station” to another using homes, churches, and businesses for refuge. The Underground Railroad symbolized both the desperate struggle for freedom by the enslaved and the moral courage of those who defied laws to help them, becoming one of the most enduring legends of American history. Wright’s work in New York City provided safe passage for escaped slaves on the vital route toward the freedom they could find northward in Canada.

Even in the face of personal danger, Wright remained steadfast. He stood against the prevailing racism of his time, challenging both the institution of slavery and the broader system of discrimination that affected free African Americans in the North. His ability to articulate a vision of justice rooted in Christian theology made him a respected and influential voice among both Black and white abolitionists.

Wright’s life serves as a reminder of the power of faith in action. His commitment to the gospel’s message of human dignity and freedom informed his work as a pastor, an abolitionist, and a conductor on the Underground Railroad. His story is one of courage, conviction, and an unwavering commitment to the cause of human freedom. Wright’s roots in Presbyterianism and his education at Princeton Theological Seminary profoundly shaped his legacy as an activist Christian. Wright’s theological training grounded him in the Reformed tradition’s emphasis on moral duty, human dignity, and the authority of Scripture. His Presbyterian faith, with its focus on justice and the sovereignty of God, fueled his conviction that slavery was a grave sin against divine law. Wright carried these beliefs into his work as a pastor at New York’s First Colored Presbyterian Church, where he preached not only spiritual salvation but also social responsibility, becoming a prominent voice in the abolitionist movement.