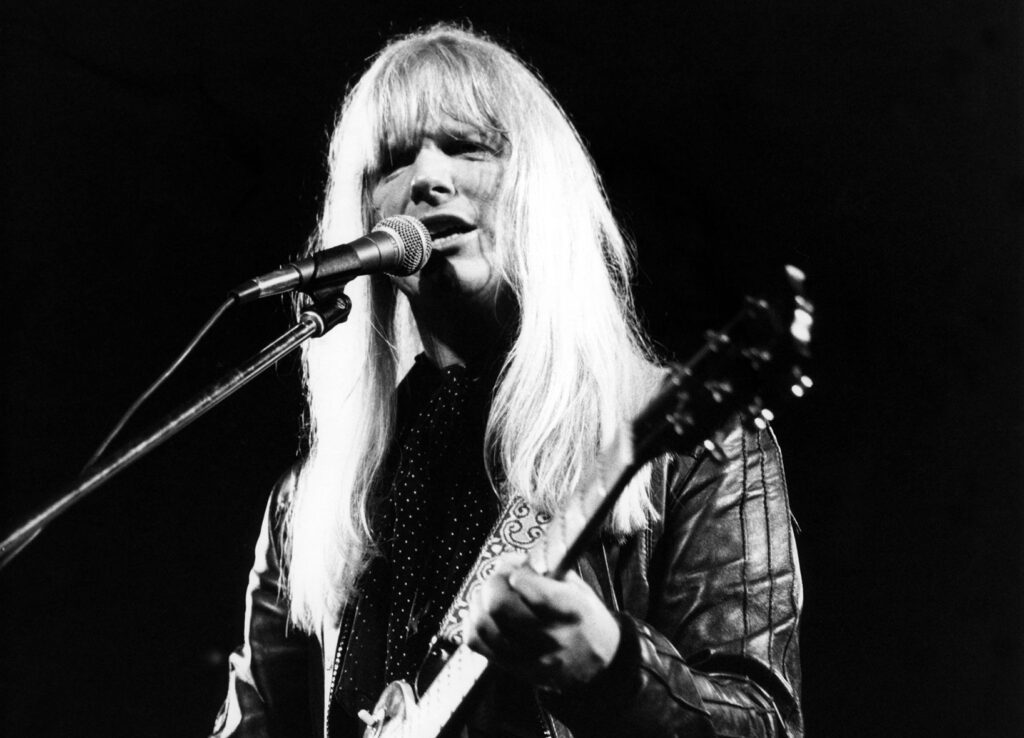

Larry Norman

April 8, 1947 - February 24, 2008

Musician and Pioneer of modern Christian music

Musician and Pioneer of modern Christian music

From Corpus Christi, Texas

Served in Los Angeles, California

Affiliation: Christian

"I'm fishing for men with a certain kind of bait, and the bait that I am offering is not a candy; it's a very specific thing that I'm offering, which is a deep gospel and a deep conversion."

In the wild swirl of the 1960s counterculture, amid long hair, protest songs, and psychedelic rebellion, a lanky young man named Larry Norman strummed a different kind of tune. His lyrics were as bold as the times, but his message pointed toward Christ. With his electric guitar and disarming honesty, Norman invented a new genre of music and helped launch a movement. Widely regarded as the “grandfather of Christian rock,” Norman was a bridge between the streetwise Jesus People and a church often uncomfortable with electric guitars and rebellion.

Born in 1947 in Corpus Christi, Texas, Norman grew up in a household that moved often and worshiped across denominational lines from Baptist to Pentecostal. Despite being born a Texan, moving to California at the age of three defined his life more directly, echoing sentiments of the freedom found on the Pacific Coast. These early years left their mark. From an early age, he experienced Christianity not as a set of rules, but as a wide-ranging faith that reached into both the spirit and the body. Music, too, came early. At age 12, Norman performed on a syndicated television show, falling in love with performance and the raw power of songwriting. For him, music was both entertainment and mission.

By the late 1960s, Norman had joined the rock band People!, a group that earned national attention and opened for acts like Janis Joplin, Van Morrison, and Jimi Hendrix. The group had a minor hit with a cover of the Zombies’ “I Love You,” and for a moment, Norman was poised for pop success. But while others chased fame, Norman was drawn to the streets. He began preaching to addicts and hippies on Hollywood Boulevard, handing out sandwiches and gospel tracts with the same intensity he brought to the stage.

Capitol Records signed Norman in hopes of turning his songwriting skills into Broadway-style musical success. But the partnership faltered. Norman’s gritty, gospel-soaked lyrics didn’t fit easily into Hollywood’s expectations. After being dropped by the label, he struck out on his own, founding One Way Records which he named for the upward-pointing finger that symbolized the message of the Jesus movement. It echoes one of Norman’s most beloved songs, “One Way.”

Norman’s music found a home in the burgeoning Christian counterculture. At festivals like Expo ’72, known by some as the “Christian Woodstock,” thousands gathered to hear messages of faith delivered with the swagger of a rock concert. In an era when many churches shunned drums and distortion, Norman asked, “Why should the devil have all the good music?” The line, taken from his most famous song, became a battle cry for a new generation of Christian musicians.

The early 1970s saw Norman release his most iconic work. Albums like Only Visiting This Planet (1972) and So Long Ago the Garden (1973) blended Dylan-esque lyrics with biting cultural critique and theological conviction. He sang about racism, poverty, drugs, and war with compassion. Songs like “The Great American Novel” and “Why Don’t You Look Into Jesus” addressed the brokenness of society, not unlike the street preachers he admired, only with a microphone and a Marshall stack.

Still, fame and faith made uneasy companions. Norman’s personal life reflected the turbulence of his times. He endured two failed marriages and recurring health problems that would plague him for decades. In later years, controversy clouded his reputation. A 2008 World magazine article accused him of fathering a child out of wedlock during a tour in Australia, a claim that some in his inner circle disputed, but that nevertheless cast a long shadow. As with many pioneers, Norman’s life did not always match the expectations of those who followed his music.

Despite this, his influence was undeniable. Norman’s raw honesty and creative daring inspired future generations of Christian artists, from dc Talk’s TobyMac to U2’s Bono, who reportedly drew from Norman’s work in shaping his own approach to faith and music. He was one of the first to argue that Christian art didn’t need to be sanitized, it needed to be truthful.

He was never fully accepted by the Christian music industry he helped create. Too rebellious for the religious establishment, too religious for the mainstream, Norman lived in the tension of being “in but not of” both worlds. He created music that confused critics and thrilled listeners, blending blues, folk, gospel, and rock in ways that hadn’t been done before.

Even as his health declined in the 1990s and early 2000s, Norman continued to write and perform. In his final years, he often appeared onstage sitting down, his voice weakened but his message unchanged. In one of his most touching lines, Norman lamented, “I wish we’d all been ready,” a reference to the rapture and the biblical end times. This lament was one that was broken for the lost souls. Until the end of his career and life, he fought with urgency to help save the lost people.

Larry Norman died in 2008 at the age of 60.

Larry Norman’s impact on Contemporary Christian Music (CCM) was foundational and transformative. As one of the first artists to blend rock music with overtly Christian themes, he broke down the barrier between sacred and secular sound, opening the door for a new generation of faith-based musicians. His bold lyrics tackled issues like war, drug abuse, and hypocrisy within the church, offering an unvarnished gospel message that resonated with the counterculture. Albums like Only Visiting This Planet set the tone for what Christian music could be which was artistic, culturally engaged, and spiritually serious. Without Norman, CCM likely wouldn’t exist in its current form

In the end, Norman was a cultural translator. He brought the gospel to people who would never step inside a sanctuary and told the church to stop running from the culture and start speaking into it. His life was messy, his music daring, and his message urgent. He may not have had all the answers, but he believed the world needed Jesus and he gave everything he had to say so.