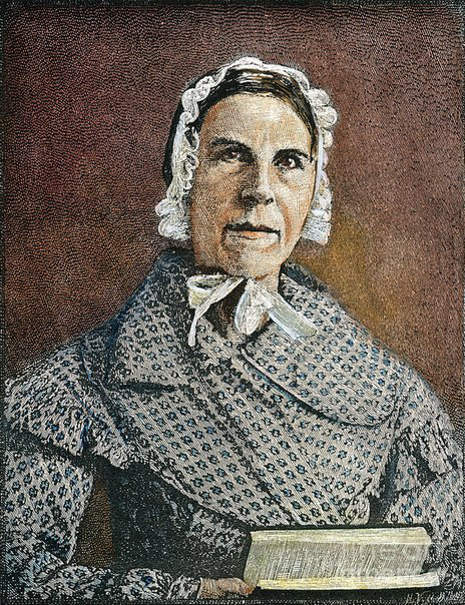

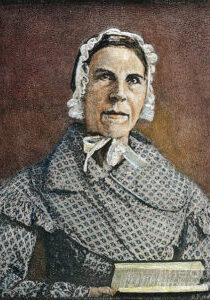

Angelina Grimké

1805 - 1879

American Abolitionist and Women's Rights Advocate

American Abolitionist and Women's Rights Advocate

From Charleston, South Carolina

Served in Hyde Park, Massachusetts

Affiliation: Quaker

“We are all bound to act, to speak, to write against the wrongs of the world, for it is our duty to do so.”

Angelina Grimke was one of the famous “Grimke Sisters,” known for their staunch women’s rights and abolitionist stances in the 19th century United States. Along with her sister Sarah, Angelina became a leading voice in two of the most significant reform movements of her time, spearheading both women’s rights and the abolition of slavery. Her life was a testament to the power of faith in action, as she drew on her spiritual convictions to challenge the oppressive systems of her era.

Born in 1805 in Charleston, South Carolina, to a wealthy, slaveholding family, Angelina Grimke grew up surrounded by the brutal realities of slavery. Witnessing the cruelty inflicted on enslaved people deeply affected her, planting the seeds of a moral opposition that would later define her life’s work. Her early environment also exposed her to the patriarchal attitudes that dominated Southern society, including those of her own father, who believed that women were inherently inferior to men.

Although raised in the Episcopal Church, Angelina’s faith journey was one of questioning and transformation. She struggled with the contradictions she saw between Christian teachings and the realities of slavery and sexism around her. Her spiritual search eventually led her to the Presbyterian Church, where she challenged its doctrines, and later to the Society of Friends (Quakers), whose commitment to equality and peace aligned with her growing abolitionist beliefs.

In 1836, she wrote her famous “Appeal to the Christian Women of the South,” a passionate letter urging Southern women to use their influence to bring an end to slavery. The letter was published by the American Anti-Slavery Society and created a firestorm. Angelina’s direct call for women to engage in the political and moral struggle against slavery was radical, even among abolitionists. Grimké’s appeal to Southern women was both powerful and provocative, rooted in her ability to speak from shared experience while challenging the moral blindness of her own community. As a woman born into a prominent South Carolina family, she understood the social expectations and limitations placed on Southern women, but she also knew the hidden horrors of slavery firsthand. Grimké called on Southern women to recognize their unique position as moral guardians of the home and to use that influence to oppose the cruelty of slavery. She argued that their faith and conscience demanded active resistance to injustice, urging them to break the silence and complicity that allowed slavery to persist. Her writings and speeches appealed to women’s sense of Christian duty, compassion, and justice, encouraging them to see abolition as not only a political cause but a deeply personal and spiritual responsibility.

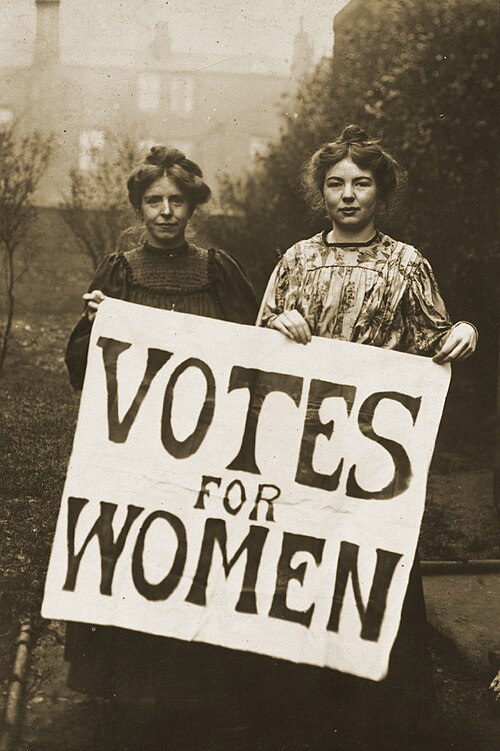

Her bold advocacy for both abolition and women’s rights led to a public exchange with Catharine Beecher, a leading voice for women’s domestic roles. Beecher argued that women should remain submissive and leave social reform to men. Grimke’s response was a fierce defense of women’s right to speak and act in matters of justice. Her writings in this debate, later published as “Letters to Catharine Beecher,” became foundational texts in the American women’s rights movement. The exchanges between Grimké and Beecher highlighted a pivotal debate over women’s roles in society and the abolitionist movement during the early 1830s. While Grimké boldly advocated for women’s right to speak publicly against slavery, grounding her arguments in Christian principles and moral duty, Beecher defended traditional views that women should focus on domestic roles and avoid political activism. Their correspondence brought national attention to the growing tension between emerging women’s rights and established social norms, challenging assumptions about gender, religion, and public engagement. Ultimately, these exchanges underscored the courage of women like Grimké who pushed the boundaries of acceptable female behavior, helping to lay the groundwork for both the abolitionist and women’s rights movements in America.

Angelina and Sarah Grimke moved north to Philadelphia, where they became active in the abolitionist movement. They were among the first women to speak publicly to “promiscuous” audiences, including crowds of both men and women, a practice that was considered scandalous at the time. Yet their eloquence and conviction won them a following.

It was at an anti-slavery training in Ohio in 1836 that Angelina met Theodore Weld, the passionate abolitionist who would become her husband. The couple’s marriage was not only a partnership in life but also in activism. Together, they wrote “American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses” (1839), a powerful compilation of firsthand accounts exposing the horrors of slavery. The book was one of the most influential anti-slavery texts of its time and heavily informed Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Angelina’s voice was not just limited to her writing. As a speaker, she challenged audiences with moral clarity, arguing that both the abolition of slavery and the recognition of women’s rights were part of a larger struggle for human dignity.

Her faith remained central to her activism. Although she left the Quaker community over disagreements about the extent of their activism, her personal spirituality continued to guide her. She saw the struggle against slavery and sexism as part of her Christian duty, believing that true faith must manifest in action. Grimké’s faith journey was marked by deep reflection and transformation, moving from the traditional religious upbringing of her Southern slaveholding family to a radical, activist Christianity that challenged the very foundations of her world. Raised in South Carolina, she was initially steeped in the culture and beliefs of the Southern elite, but her exposure to the brutal realities of slavery awakened a profound moral crisis. Embracing a fervent evangelical faith, Grimké came to see abolition as a divine imperative. Her faith led her north, where she became one of the first women to speak publicly against slavery and advocate for women’s rights, often facing fierce opposition. Throughout her life, Grimké wrestled with the tensions between social convention, religious doctrine, and personal conviction, ultimately forging a path that integrated faith, justice, and reform in ways that challenged both church and society.

Angelina Grimke’s legacy is that of a courageous woman who refused to remain silent in the face of injustice. Her life and work serve as a powerful example of how faith, when coupled with moral courage, can become a force for transformative change.