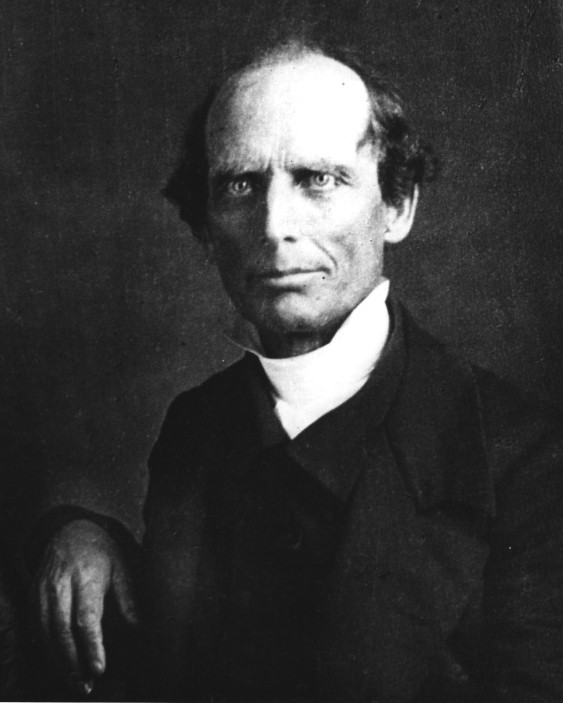

Charles Finney

August 29, 1792 - August 16, 1875

Pastor, Educator, Theologian, and Founder of Oberlin College

Pastor, Educator, Theologian, and Founder of Oberlin College

From Warren, Connecticut

Served in Oberlin, Ohio

Affiliation: Congregational

"A revival may be expected when Christians have a spirit of prayer for a revival. That is, when they pray as if their hearts were set upon it. When Christians have the spirit of prayer for a revival. When they go about groaning out their hearts desire. When they have real travail of soul."

Charles Grandison Finney was one of the most influential figures of the Second Great Awakening, a man whose faith was not merely a private conviction but a force that reshaped the moral landscape of the United States. His preaching, revival meetings, and later academic career at Oberlin College were all animated by a singular belief: that Christianity was not a passive faith but an active, transformative power meant to change both individual souls and the society in which they lived.

Finney’s personal journey to faith was as dramatic as the revivals he would later lead. In 1821, while studying law, he experienced a sudden and profound conversion. “The Holy Spirit seemed to go through me, body and soul,” he later recalled, “I could feel the impression, like a wave of electricity, going through and through me.” This encounter led him to abandon his legal career and commit himself fully to preaching the Gospel. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Finney did not see Christianity as merely a matter of personal salvation; he believed in its power to bring about tangible change in society.

This belief found full expression in the revivals he led throughout the 1820s and 1830s. His meetings were unlike the staid, formal church services of the past. He encouraged public testimonies, invited sinners to the “anxious bench” at the front of the congregation, and called for immediate, life-changing decisions. “Religion is the work of man,” he declared. “It is something for man to do.” Faith, in his view, was not a quiet reflection but an active commitment to righteousness and justice.

His theology was deeply practical. To Finney, true conversion had to be followed by a reformation of character and conduct. He challenged his listeners to live out their faith by confronting the great sins of their age, particularly slavery. His disdain for slavery directed his path to Oberlin College in central Ohio where he served as an ardent abolitionist.

Oberlin College, where Finney became a professor and later president, was founded on these same principles. Under his leadership, it became the first college in the United States to admit both Black students and women on an equal footing with white men. Oberlin also became a key stop on the Underground Railroad, its students and faculty risking their safety to aid those fleeing bondage. For Finney, such activism was inseparable from Christian duty.

His influence extended far beyond the walls of Oberlin. The wave of religious revival he helped to spark had profound social consequences. Thousands who experienced conversion under his preaching became passionate advocates for reform. Many abolitionists, temperance leaders, and early advocates for women’s rights traced their activism back to the moment they first heard Finney speak.

Historian Mark Noll has described the Civil War as a “theological crisis,” and Finney’s impact on that crisis cannot be overstated. The South’s pro-slavery theology stood in stark contrast to the faith-infused abolitionism of the North—a division fueled in part by Finney’s relentless moral clarity.

Yet, for all his radicalism, Finney was no mere political agitator. His central message was always one of personal transformation. He did not advocate social reform for its own sake, but because he believed that a truly converted heart could not abide injustice. He saw revivals as God’s means of awakening both individual souls and national conscience. “A revival is nothing else than a new beginning of obedience to God,” he wrote. And that obedience, he taught, demanded both prayer and action.

When we talk about slaveholders of faith, we point out that there were different interpretations of scripture. So too it is important to mention that there were many, particularly southerners, who did not agree with Finney’s perspective on slavery. Many with a paternalistic view of slavery believed that they were in the right to “help” slaves, to Christianize them through paternal guidance. While Finney did not agree with this perspective and found the treatment of slaves to be abhorrent, herein was the debate at the time. With respect to Noll’s argument, the theological crisis of the Civil War centered on the interpretation of scripture regarding the role of slavery in American society with the abolitionists of the North taking a Finneyite abolitionist view and the slaveholders of the South taking a paternalistic pro-slavery view. That was, according to historian Chandra Manning, what the “cruel war was over.”

His influence continued long after his death in 1875. The institutions he helped shape, the lives he touched, and the movements he inspired carried forward his vision of an engaged, activist Christianity. The Second Great Awakening was not merely a religious revival—it was a redefinition of American faith, one in which belief was measured not only by one’s prayers but by one’s deeds.

Charles Grandison Finney’s life and work remain a testament to the power of conviction. His was a faith that moved mountains, not by waiting for divine intervention, but by calling upon men and women to act as instruments of justice and mercy. In a time of national turmoil, he stood as a beacon of moral clarity, insisting that true faith could never be content with passivity. It had to be lived—and it had to change the world.

For further reading:

Hatch, Nathan. The Democratization of American Christianity. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991).

Noll, Mark. The Civil War as a Theological Crisis. (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2015 reprint)