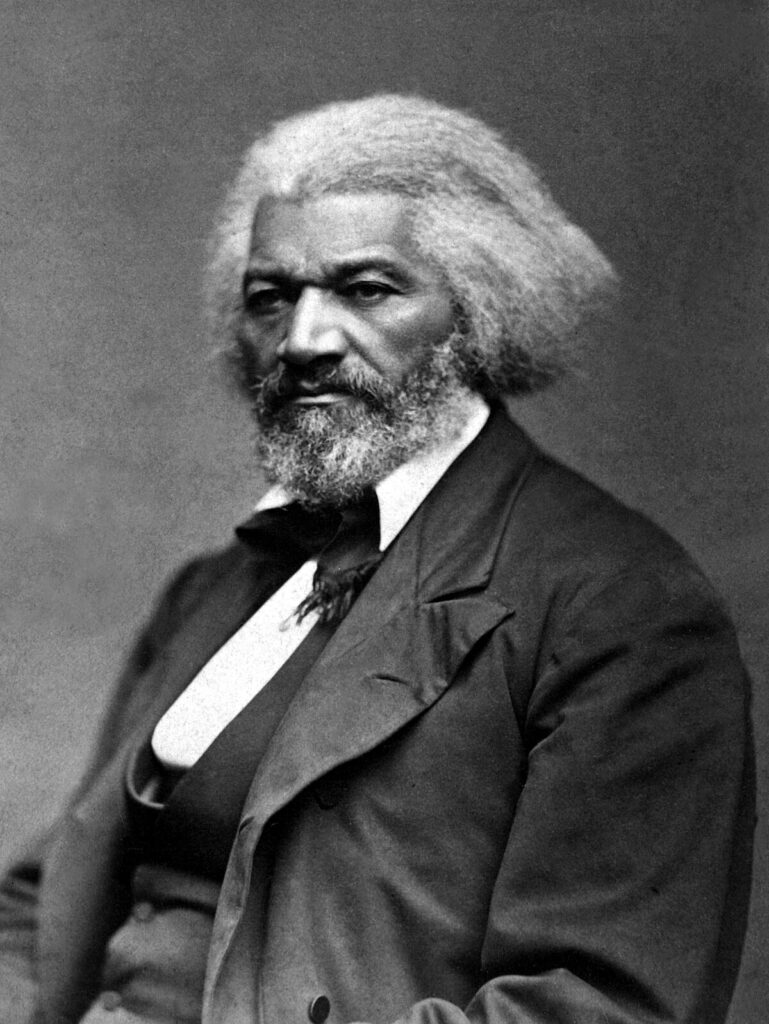

Frederick Douglass

February 14, 1818 - February 20, 1895

Abolitionist, Politician, and Author

Abolitionist, Politician, and Author

From Cordova, Maryland

Served in Washington DC

Affiliation: African Methodist Episcopal

"I love the pure, peaceable, and impartial Christianity of Christ: I therefore hate the corrupt, slaveholding, women-whipping, cradle-plundering, partial and hypocritical Christianity of this land."

Frederick Douglass was one of the most important figures of the 19th century, known for his role in the abolitionist movement and for becoming an internationally renowned spokesperson for freedom and equality. Born into slavery, Douglass escaped to the North, where he became a powerful voice for the enslaved and a fierce advocate for the abolition of slavery. His impassioned speeches captivated audiences across the United States and abroad, with his own life story serving as the most powerful testimony to the possibility of African American equality. Yet, Douglass’s relationship with Christianity was complex and deeply personal. Though his faith was not typical, it was infused with a prophetic moralism, grounded in spiritual conviction, and framed by the tension between the gospel of liberation and the religion used to justify oppression. Douglass famously drew a sharp distinction between what he called the “Christianity of Christ” and the “Christianity of this land,” condemning the latter as a tool of injustice while embracing the former as a transformative force for justice. This distinction helped to shape his public voice, which, like the voice of an Old Testament prophet, carried a tone of both judgment and hope.

Douglass’s early experiences with Christianity were inextricably linked to the brutal realities of slavery. As a child, he first encountered Christian teachings through the slaveholder’s version of the Bible, but it was not long before Douglass recognized the ways in which Christian doctrine was distorted to uphold the institution of slavery. White preachers, he wrote, taught slaves to accept their status as inferior, twisting biblical teachings to justify their exploitation. This early exposure to Christianity left Douglass with a deep bitterness, as he struggled to reconcile the teachings of Christ with the reality of enslavement. Yet, even in the face of this contradiction, he began to see the potential of Christianity as a source of hope. In time, his encounters with the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church deepened his understanding of Christianity as a religion of resistance, one that could empower both the individual and the community in the fight for liberation. As Douglass came to see it, Christianity was a weapon in the struggle against the moral evils of slavery. His most intimate reflections on this complex relationship with faith can be found in Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, a work that has been published in several editions, but which consistently highlights his eventual embrace of Christianity as a source of both personal and social transformation.

As Douglass’s voice became a leading one in national debates, his faith grew in prominence, transforming him into a moral voice calling the nation to repentance. By the time of his most famous speeches, including his 1852 oration, What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?, Douglass had become a towering figure, using his platform to hold America accountable to its ideals of freedom and equality. Douglass’s message in this speech was as blistering as it was prophetic, pointing out the hypocrisy of a nation that celebrated liberty while holding millions of people in slavery. Drawing on rich biblical imagery, he likened the nation’s moral failings to the sins of ancient Israel, condemning the nation for its refusal to live up to the Christian ideals it professed to hold dear. Douglass’s denunciation of American slavery was rooted in the belief that the nation had turned its back on the true gospel of Christ, a gospel of justice, liberty, and equality for all people. His speeches, though deeply moral in tone, were also filled with a sense of urgency, a prophetic call for national repentance, for a reckoning with the nation’s sin and hypocrisy.

In his later years, particularly after the Civil War, Douglass’s faith underwent a transformation. The horrors of slavery and the complex struggles of freedom left deep marks on him, and his reflections on faith became more personal, inward, and philosophical. Historian David Blight, in his seminal work Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, argues that Douglass wrestled with a profound sense of existential doubt in the years following emancipation. Despite his continued public commitment to justice, Douglass’s internal life was marked by a search for spiritual rest and reconciliation. His faith, which had once been a clarion call for social change, became more reflective, as he sought to make sense of the evil he had witnessed and endured. The once-uncompromising moral clarity of his earlier years gave way to a more nuanced understanding of God’s will and divine providence. While Douglass never abandoned his moral convictions, his private reflections on the nature of God’s justice and the problem of suffering in a world marred by evil became a key aspect of his spiritual journey.

Douglass’s religious convictions extended into his broader vision of what America could and should become. He believed the nation was capable of moral regeneration, but only if it turned away from hypocrisy and embraced the true spirit of its founding ideals. In numerous addresses, he challenged churches to take a stand for justice, insisting that silence in the face of slavery and racial inequality was complicity. He did not hesitate to call out religious leaders and institutions for their moral cowardice, but he also held out hope that religion, when rightly practiced, could play a redemptive role in American life. Douglass’s emphasis on moral accountability, civic virtue, and spiritual courage spoke to a broader audience than abolitionists alone. He became a statesman of conscience, urging Americans to pursue a “more perfect union,” as Abraham Lincoln phrased it, not only through political means but through a renewal of the nation’s moral and spiritual foundations. In doing so, he helped shape a religious and civic discourse that would echo far beyond his lifetime, influencing movements for justice well into the 20th and 21st centuries.

Through his life and work, Douglass demonstrated that faith could be both a source of personal transformation and a powerful tool for social change. His prophetic vision of Christianity, though deeply rooted in his own experience as a former slave, transcended his individual story, offering a vision for a nation that had yet to fulfill the promises of liberty and equality it claimed to uphold. Douglass’s legacy as both an abolitionist and a prophetic Christian continues to inspire those who believe in the power of faith to bring about justice, healing, and reconciliation.

For further reading:

1. Blight, David W. Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018.

2. Levine, Robert S. The Lives of Frederick Douglass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016.

3. Stauffer, John. Giants: The Parallel Lives of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. New York: Twelve, 2008.