"I should be sorry if I only entertained them, I wish to make them better."

Superlatives are often ascribed to those whom others wish to flatter. Rarely does the description of one’s person or work match the compliment given. One indication of authentic praise is when it comes from peers who know a person intimately or understand fully the intricacies of one’s profession.

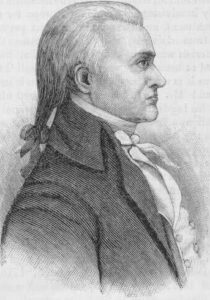

Such is the case with the contemporaries of George Frideric Handel. Haydn, Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven viewed him with awe and deep adulation. It is reported Beethoven said, “Handel is the greatest composer ever.” Mozart allegedly said if he had the choice to be born any other composer, he would wish to be born Handel. And according to friends, Haydn said, after attending a performance of one of Handel’s compositions, “He is master of us all.”

In Halle, Saxony (Germany), George Frideric Handel was born on February 23, 1685. His father, Georg Handel, was a barber-surgeon. He served the Courts of Saxony and Brandenburg and also contributed to public health and forensic medicine. His mother, Dorothea Taust, was the parent who recognized young George’s gifts and nurtured them early on. His father wished for George to follow him into the field of medicine desiring what he deemed the best for his son.

His aunt, Anna, also contributed to his musical development. She gifted him on his 7th birthday a small harpsicord, a spinet. It was placed secretly in the attic in a tiny room. At night, as everyone slept, Handel would quietly steal away to the room and practice.

Handel’s love of music grew throughout his childhood, but “it” almost killed him when he was 19 years of age. During a performance of The Misfortune of Cleopatra, he and his friend, Johann Mattheson, entangled themselves in an argument about who would lead the remainder of the opera after Mattheson’s character was killed in the third act. Handel had assumed the role of conductor after the original conductor abruptly vacated his duty half way through the opera. (The composer, Reinhold Keiser, was known for his alcoholism. This might have been the cause for his departure.) After the curtains fell, the argument continued and boiled over into a sword duelin the market square. Handel almost lost his life. A button on his coat deflected a near-lethal thrust from Mattheson. The two eventually reconciled and remained friends.

This was not the only time Handel’s anger would be remembered long past his lifetime. In London, years later, he became incensed by Frecesca Cuzzoni’s refusal to follow his directionduring rehearsal. He grabbed her by the waist and threatened to throw her out an open window. He also screamed at her, “I know that you are a real she-devil, but I will have you know that I am Beelzebub!”

Early in his childhood, Handel’s musical giftedness was recognized. On a particular journey he and his father took to Weissenfels to visit the Duke of Saxe-Weissenfels, the boy played the organ for the royal. The duke, quite impressed, encouraged his father to facilitate the lad’s musical interests. Weissenfels would become Handel’s musical education center. There he was exposed to the Nürnberg master, Johann Krieger and opera’s allure. In time, he began studying under the composter Friedrich Zachow in Halle.

Tragedy visited the Handel family in 1697 when his father died at 75 years of age. Georg had planned for young George’s education and in 1702 he enrolled at the University of Halle to study law. While at university, he also was the organist for the Reformed Cathedral. A year later, he left university and moved to Hamburg in hopes of furthering his musical talents and opportunities. He made do as a back-desk violinist at the opera house. In time, he assumed the duties of harpsichordist. His musical investment paid off in 1705 when his first opera, Almira, premiered in Hamburg.

From 1706-10, Handel continued to build his resumé traveling Italy. He composed ecclesial, secular, and theatrical pieces for patrons in Rome, Florence, Venice, and Naples. Agrippina was a very successful opera that premiered in 1710 in Venice and gained him international acclaim. While in Italy, his musical style was shaped by Italian composers such as Arcangelo Corelli, Domenico Scarlatti, and numerous others.

His path to becoming one of Britain’s most famous and beloved composers began with the elector (German prince) of Hanover, the future King George I. England was thoroughly put out with being ruled by Catholic monarchs. Therefore, in 1701, Parliament passed the Act of Settlement and this resulted in the House of Hanover being chosen as the future royal bloodline. The descendants of this house hailed from King James I (1603-25). In 1710, the elector, George Louis of Brunswick-Lüneburg, selected Handel to be kapellmeister, the conductor of his court’s chamber orchestra.

As Agrippina had won over the hearts of Italians, Rinaldo, specifically composed for London,captured the hearts of the city. Handel considered the reception of the work as a promising omen of future success in England. He returned to Hanover for a short time in 1711 and moved permanently to London the next year. In 1713, he earned himself an annual allowance of £200 from Queen Anne with “Ode for the Queen’s Birthday” and “Utrecht Te Deum and Jubilate.” The latter composition celebrated the Peace of Utrecht which ended the War of the Spanish Succession.

The following year, the queen died and George Louis ascended to the throne of England. Success and appointments continued for Handel. In 1718, Handel was appointed director of music to Henry James Brydges, the Duke of Chandos. The next year, he became the music director of the Royal Academy of Music. The newly formed company’s mission was to establish Italian opera in the city.

In February 1727, the German-born composer became a subject of the king of England. This reality opened up more doors for Handel. He the Chapel Royal’s composer and wrote numerous pieces. Those of note would be the coronation anthems for King George II, which includes “Zadok the Priest” and the funeral anthem for Queen Caroline ten years later.

A shift took place in the musical landscape of London in 1728. John Gay’s Beggar’s Operapremiered in London, an opera ballad that mixed high art with low art. Lyrics were written in English with melodies pulled from English, Scottish, French, and Irish heritage. It also revealed the degeneracy of London’s elite by laying out its parallels with opera’s protagonists. Thus, operas began to fade in popularity also because of the performers’ lack of a moral compass. Despite the genre’s decline, Handel continued to compose operatic pieces until 1741.

The oratorio soon became the popular music form for London audiences. Early on, two of Handel’s oratorios were well-attended, “Acis and Galatea” and “Esther.” The latter, however, was less popular with the church surprisingly. It was criticized because thespians were portraying a story from the Bible and the very words of God were being recited in a house of drama and not one of God. Opposition also came from the leadership of the Church of England in London. The bishop declared the oratorio should not be performed. Handel ignored the edict and the royal family attended. Esther became a success.

With success, there was also difficulty. The Italian opera company Handel comanaged was a business venture that was a struggle to maintain. Competition from other composers and opera houses made success elusive due to the limited appetite for Italian opera in London. In 1737, the company went bankrupt. Near the same time, he suffered a stroke. His right arm was paralyzed due to the event. His doctor was not optimistic about Handel regaining use of the arm. “We may save the man—but the musician is lost forever. It seems to me that his brain has been permanently injured,” the physician declared. It is thought this was just one stroke of others he suffered after the summer of 1737.

Determine to regain use of his arm, Handel traveled to Aachen, Germany to seek help. The treatment and his determination are credited for restoring his health to fullness. Upon recovery, he declared, “I have come back from Hades.” He composed his most acclaimed oratorios after the stroke. In 1739, “Saul” and “Israel in Egypt” were performed. And two years later, his most famous oratorio, “Messiah.” Of note, regarding “Israel in Egypt,” he revised it after audience feedback. At first, it was not given much praise so he added some flourishes with ear-catching solos and trimmed the number of choruses. The edits paid off.

From these three oratorios and others, Handel’s content strategy emerges. Near the end of writing operatic pieces and after, he used stories from the Bible as the content for oratorios. This aligned with the Protestant sensibilities of concert goers in light of the religious revival taking place in England. The audiences would have been quite familiar with the Old and New Testaments.

Despite the successes of “Saul” and “Israel in Egypt,” Handel was depressed and in financial straits in 1741. His friend, Charles Jennens, paid him a visit. He had written a libretto about Christ’s life, death, and resurrection with texts culled from the holy scriptures. The devout Anglican had written it as a defense of Jesus’ divinity and against deism. He asked Handel to compose music for it. Handel obliged and believed he would be able to complete it in twelve months.

During this period of England’s history, deism was a widely held belief that threatened orthodox Christian faith. Deism taught God is not a personal God, but a being who began the universe and then “stepped back” and merely observes what transpires on earth.

Handel composed the 260-page work at a frenetic pace completing it in 24 days. During the time of composition, he sequestered himself in his room and barely ate. The completed work has been hailed as “an epitome of Christian faith.” At the end of writing Messiah, he said, “I did think I did see all Heaven before me, and the great God himself, with His company of Angels!”

The first performance was in Dublin, Ireland. Handel organized the performance to benefit those in a debtors’ prison. 700 people packed Fishamble Street Musick Hall on April 13, 1742 to hear the first public performance of the “Hallelujah Chorus” and the rest of Handel’s musical triumph. Organizers did all they could to accommodate the overcapacity crowd. Women were forbidden to wear hoops in their skirts (a popular fashion of the day). Men were notified not to wear swords.

The premiere brought in receipts of £400, which paid the debts of 142 men who were then released. Of course, there was also some controversy regarding the oratorio. Jonathan Swift, author of Gulliver’s Travels and dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral’s choir, did not want any chorus member of the Cathedral to perform in a music hall for he feared it would dishonor the choir’s reputation. He also was against contralto Susannah Cibber participating in light of her recent,scandalous divorce. Swift eventually dropped his opposition to the performance.

Almost a year passed before Messiah was performed in London. Controversy again plagued theHandel production. Overall, biblical oratorios were viewed as profane because it was believed scripture should not be placed in a dramatic or musical setting. To quell the controversy regarding Messiah, Handel changed the “blasphemous” title to A New Sacred Oratorio. The kerfuffle did not prevent King George II from attending. After its premiere, the oratorio did not fare well.

Other oratorios of Handel’s also were met with lukewarm reception. By 1745, Belshazzar, Semele, Hercules, and other works suffered from low attendance. Consequently, he was suffering greatly from a financial standpoint. Judas Maccabeus rescued him from poverty in 1746. The production commemorating the victory of the English over the Jacobites at the Battle of Culloden. The story of the Jewish leader was used as a parallel for the events of the conflict.

In 1749, Handel once again coordinated a performance of Messiah for a charitable cause. This time it was to complete the construction of London Foundling Hospital, a facility for abandoned infants and children. It began a succession of annual benefit performances of Messiah at Easter time until the 1770s. He conducted or attended all of them ‘til his death.

In the final decade of his life, Handel’s health faltered. The causes range from poor medical practice to a series of more strokes to lead poisoning. As he aged, his eyesight was impacted by cataracts. He underwent a procedure several times that was meant to restore his vision, but it slowly destroyed it. An instance of irony is he wrote Samson as his vision was failing. One specific line is “Total eclipse. No sun, no moon, all dark.” In regards to lead poisoning, the wine he drank was stored in lead containers. When it arrived from southern Europe, it was sweetened with lead to boost the wine’s flavor profile and stabilize it. In light of Handel’s love of wine, it is presumed he suffered from lead poisoning.

***

In society’s eyes, Handel had much to boast about, but in light of his reverence for his Creator, he would not take the credit. In 1759, whilst receiving a rapturous ovation after his last performance Handel cried out: “Not from me… but from Heaven… comes all.” In another instance, Handel demonstrated his love and affection for his Redeemer as he approached his final days on earth. He remarked he desired to die on Good Friday “in the hope of rejoining the good God, my sweet Lord and Savior, on the day of His resurrection.” He died on Easter Saturday, April 14, 1759. Beloved by the English for his contribution to its culture, he was given a state funeral and was buried at Westminster Abbey next to Charles Dickens. A statue of him by his grave commemorates his life with lyrics from Messiah inscribed: “I know that my Redeemer liveth.”

In many ways, Handel fits the mold of exemplary actions for the sake of the kingdom of God mixed with the repugnance of personal flaws. One moment of his life he provided an astounding musical setting for the very words of God. In another period, he manifested childish fits of rage by dueling over a petty dispute. And yet in another instance, he manhandled a woman in his choir and threatened her with physical violence. In the same man resided a heart of charity and yet a heart of self-indulgence. Only by the grace of God was treasure found in this “earthen vessel.”

George Frideric Handel lived to be 74 years of age.

SOURCES: BBC Music, Britannica, GFHandel.org, Gordon College, Christian Heritage Edinburgh, Christianity Today, Christian Post, The Tabernacle Choir, Patheos, George Frideric Handel, and The Gospel Coalition.