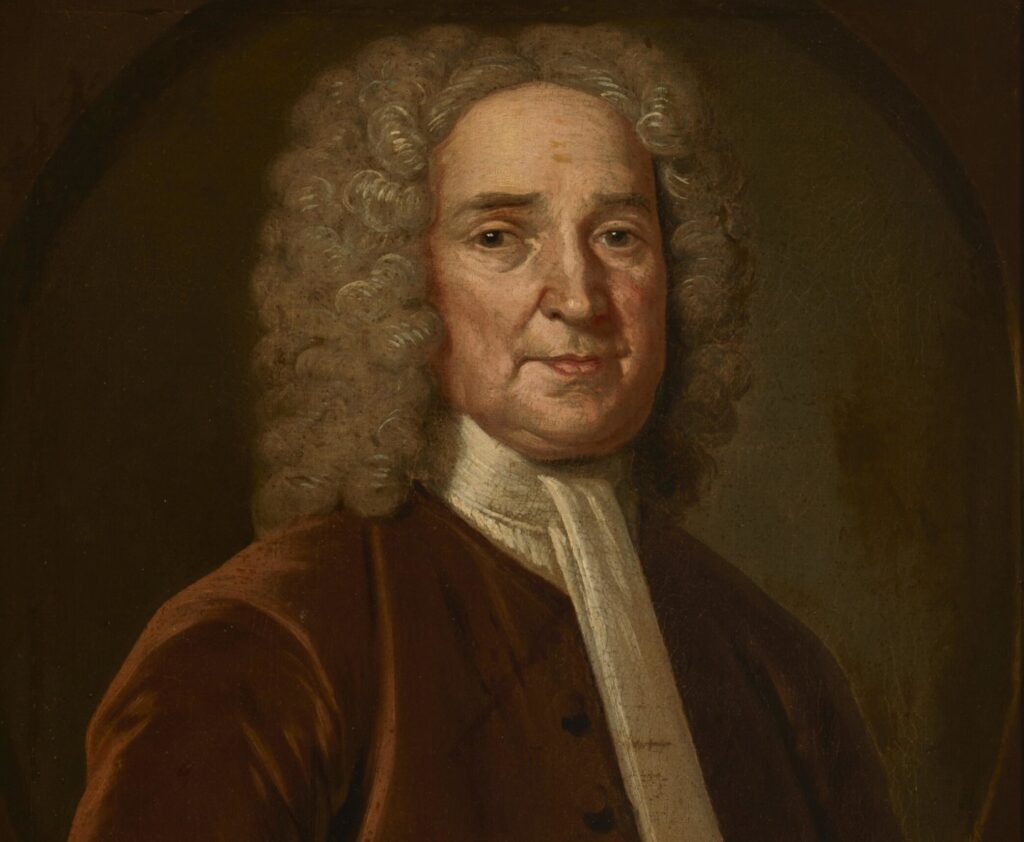

Isaac Backus

January 9, 1724 - November 20, 1806

Baptist Preacher who campaigned against state-established churches in New England and helped to found Brown University

Baptist Preacher who campaigned against state-established churches in New England and helped to found Brown University

From Norwich, Connecticut

Served in Middleborough, Massachusetts

Affiliation: Baptist

"The scheme we oppose evidently tends to destroy the purity and life of religion; for the inspired apostle assures us, that the church is espoused as a chaste virgin to Christ, and is obliged to be subject to him in every thing, as a true wife is to her husband."

During the American Revolution, numerous men assisted in forging the United States. Only a handful of men, however, contributed significantly to building the philosophical foundations of both the new government and a new church denomination.

Isaac Backus was a founder of the Baptist denomination, which grew out of the American Congregationalist Church. It is currently the largest Protestant denomination and arguably the most influential in shaping America over the past century. Rev. Backus also contributed significantly to the development of freedom of religion and its inclusion in the United States Constitution. Finally, the New England preacher applied Jonathan Edwards’ theology of original sin to the political realm in his political theology of religious toleration, according to Brandon J. O’Brien.

Rev. Backus was born on January 9, 1724 in Norwich, Connecticut. The Backus family was integral to the leadership of Norwich since its founding in 1660. A number of the reverend’s ancestors held various public offices including his father, Samuel Backus, who served in the town assembly. He died when Isaac was 16 years of age leaving his wife to raise ten children and a six-week-old infant. His family has been described as nominal Congregationalist.

After the British evangelist, George Whitefield, had completed his first tour in New England in 1741, young Backus attended a meeting where one of Rev. Whitefield’s sermons was read. During the meeting, he experienced an indication of regeneration. He described it thusly, “the Lord was pleased to give me some sweet sealing of the Holy Spirit of promise.” Following conversion, he gained an understanding of the Christian faith by reading the works of Jonathan Edwards. Backus and his family became known as “New Lights” along with others who embraced the revival that was taking place. (The “Old Lights” were Christians who opposed the spiritual revival taking place at the time.) They separated from the Congregationalist churches or the Standing Church as it was also known.

Isaac Backus, however, did not join a church immediately. He believed there to be “many corruptions among them.” After almost a year, he joined the Standing Church in Norwich. Yet, after about 18 months, he surmised they had “a form of godliness, but den[ied] the power thereof.” Therefore he and nine others, including his mother and brother, covenanted together and established the Bean Hill Separate Church in Norwich. He felt called to preach and did despite not being approved by leaders from the Congregationalist Church. At the same time, he began traveling to local and regional churches to preach. Backus was ordained in 1748. A year later he married Susannah Mason of Rehoboth. They had nine children. Of note, Backus officiated his own wedding.

While leading the congregation in Norwich he began preaching regularly in homes in Titicut, Massachusetts. On February 16, 1747, Rev. Backus and 16 others organized the Titicut Separate Church. He did so without the approval of the Standing Church committee. New ministers were expected to be approved by a committee of existing ministers. Backus and other Separatist preachers felt strongly the only approval they needed for their calling to preach the Word of God was God’s. Man did not need the approval of the Standing Church committee who weighed a man’s education and other aspects of his life to determine his fitness to preach.

In time, Rev. Backus and some of his parishioners were torn about people receiving communion who had been only baptized as infants before they had reached an age of understanding, believed, and been baptized after being converted. The permittance of those who received infant baptism (pedobaptism) to participate in the Lord’s Supper is called open communion. It was the common practice of Separate churches at the time who accepted both pedobaptism and credobaptism (believer’s baptism). Consequently, it was not uncommon for congregants to quibble about who should and should not be refused the cup and the bread. Furthermore, some considered infant baptism an act of making a person wet and nothing more. Others went as far to call it a sin.

Backus came to the conclusion one should only partake in the Lord’s Supper if the person has believed and then been baptized (closed communion). Hence, he dissolved the Titicut Separate Church after eight years.

On January 16, 1756, 32-year-old Isaac Backus, his wife, and four others formed the First Baptist Church of Middleborough. Concurrently, Backus helped another church navigate the contentious issue of communion participation. This was the first of many Separate and Baptist churches he advised not only on this issue, but also on other ecclesial matters. He also occasionally ordained pastors in these churches. For 50 years, he led the congregation at the Middleborough church.

A manner in which Backus helped establish the Baptist denomination was his assistance in forming a local association of Baptist churches in Massachusetts in 1767. Eventually, the Warren Baptist Association formed a Grievance Committee, which Backus chaired. The committeerepresented concerns of the churches to the local authorities. Most notable of these concerns was the certificate law which required a certificate of validation from three older Baptist (Anabaptist) churches for a new Baptist church. The Massachusetts legislature hoped this process would unify the two sets of churches. While the Separate churches were young in existence, the Anabaptist churches had roots in the 16th century in Switzerland and other parts of Europe.

Rev. Backus advocated to the government people did not gain their right to choose to worship from the state. It was a natural right granted by God. The certificate system was “taxation without representation,” he declared, borrowing verbiage from other colonists fighting for independence the British government. Out of this issue, he formed his theory of separation of church and state. He wrote in his pamphlet, An Appeal to the Public for Religious Liberty, God has established a civil government and an ecclesial government. “The civil government is left to human discretion, and our submission thereto is required under the name of their being, the ordinances of men for the Lord’s sake. … Whereas in ecclesiastical affairs we are most solemnly warned not to be subject to ordinances, after the doctrines and commandments of men.”

Isaac Backus continued to advocate for religious liberty in other forums. In 1774, he appeared before and appealed to the representatives of the 13 colonies at the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia. He also promoted the issue in pamphlets, sermons, newspapers, and petitions. His thinking also influenced James Madison’s draft of the Bill of Rights.

Rev. Backus also advocated that the government not tax the colonists in order to support churches. Firstly, he believed the government did not have the right to tax for the benefit of religious institutions. Secondly, he refused to pay the tax for he believed that to pay the tax communicated the government had a right to collect it. To him, civil disobedience was mandatory. He was convinced no person should be compelled to support other churches with tax money and government should not support one religious group over another religious group. “It’s not the pence but the power that alarms us,” he wrote. He proposed all colonists refuse to pay the tax. Thirdly, Backus raised funds to pay for the legal expenses of those who refused to pay the tax and were jailed for their refusal. He also sought funds to recover seized property and compensation for lost wages. Backus, his mother, and others were jailed for not paying the religious taxes. Some Baptists in Ashfield, Massachusetts suffered greatly for their refusal. They had property seized and orchards destroyed.

Despite being against the government on this matter, Isaac Backus was supportive of the government’s action to seek political independence from England. A sermon he preached 12 days after the battles of Lexington and Concord “breathed as much fire and patriotism as any sermon preached from a Congregationalist pulpit.” It is recorded he “urged full cooperation with the American government.” Between King George III’s permitting Catholicism in Quebec and the Parliament confiscating colonist’s property, Backus was supportive of rebelling against a government that had broken trust.

After the War for Independence had been won, Rev. Backus again engaged in service to his nation when he delegated at the Massachusetts convention for the ratification of the United States Constitution. Many of his fellow delegates did not support ratification, but he did and voted thusly. He would see the adoption of the Bill of Rights in 1791 and the enactment of religious liberty as the law of the land. He would not see, however, the abolishing of state-funded Congregationalist Churches, which took place in 1833. Backus died in 1806.

It appears Isaac Backus began slowing down in 1799. In this year, on September 2nd, he ceased teaching at Rhode Island College (now Brown University). (Two years earlier, he had been awarded an honorary degree by the institution.) Then in 1800, he only traveled 121 miles and preached 113 sermons. These numbers are significantly lower than totals from previous years. For instance, he journeyed 1,369 miles and preached 148 sermons in 1788. The year before that, he traveled a little less, 1,328 miles, but preached a little more, 158 sermons. The most came in 1789 when he trekked to North Carolina and Virginia in addition to his regular travel. For this year, he logged 1,895 miles by land and 1,280 by water and preached 190 times.

In addition to impacting many lives through his preaching, Rev. Backus also wrote about the church and some of her doctrines (election, perseverance, sovereign grace, and more). He also wrote a three-volume history of New England Baptists entitled, History of New England, with Particular Reference to the Denomination of Christians Called Baptists.

The religious liberty fighter had two strokes in the spring of 1806. The first was mild. The second was worse. He fought to be healthy again. His mind permitted him to preach a little more, but not for long. He preached his final sermon on April 3rd. He succumbed to poor health and died on November 20th of the same year.

***

Rev. Backus held a deep love for Christ’s bride, the Church, in his heart. He traveled through sunshine and rainstorms, across trailless land, and in extreme temperatures in order to teach numerous Christians and evangelize the unconverted. An example of his devotion is the three-year stretch mentioned earlier. During this period of time, he traveled over 4,500 miles by horse or boat. He also expressed his love for the Church by fighting for her religious freedom and her independence from the government.

Isaac Backus lived to be 82 years of age.

SOURCES: Southern Baptist Historical Library & Archives, Christianity Today, and Center for Baptist Renewal