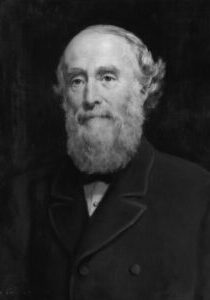

Lyman Beecher

October 12, 1775 - January 10, 1863

Pastor

Pastor

From New Haven, Connecticut Colony

Served in Brooklyn, New York and Cincinnati, Ohio

Affiliation: Congregational

"Intemperance is the sin of our land, and, with our boundless prosperity, is coming in upon us like a flood; and if anything shall defeat the hopes of the world, which hang upon our experiment of civil liberty, it is that river of fire, which is rolling through the land, destroying the vital air, and extending around an atmosphere of death."

Lyman Beecher was one of the most influential religious figures in 19th-century America, a man whose theological convictions and activism helped shape the course of American history. Rooted in the fervor of the Second Great Awakening, Beecher emerged as a powerful voice in the religious revival movement that swept across the United States in the early 1800s. His passionate preaching, which called for both personal and social reform, made him a central figure in the Evangelical wing of American Protestantism. Beecher was not merely a preacher, but a moral architect of his time, offering a vision of society that emphasized individual responsibility, the importance of personal virtue, and the transformative power of faith. He became widely known for his emotional, stirring sermons that addressed issues of sin, salvation, and the pressing need for societal change, especially in the context of slavery and temperance.

Born in 1775 in New Haven, Connecticut, Lyman Beecher grew up in a time of profound social and political upheaval, as the United States was in the process of defining itself as an independent nation. Raised in a devout New England family, Beecher’s early life was shaped by the religious and intellectual currents of the age. He attended Yale College, where he studied under the guidance of the renowned theologian Timothy Dwight. His formal education and exposure to the intellectual ferment of the time gave Beecher the tools to become a leading voice in the emerging religious movements of the early republic.

Beecher’s theological views were heavily influenced by the New Light tradition of American Calvinism, which embraced revivalism and personal religious experience, but with a focus on moral agency. Unlike the more rigid “Old Light” Calvinists, who adhered strictly to the doctrine of predestination, Beecher believed that individuals had the moral freedom to choose salvation. This belief in human agency, which softened traditional Calvinist predestination, became a cornerstone of his theology. Beecher’s system of thought, often referred to as “New England Theology” or “moral government theology,” held that God ruled the universe as a moral governor and humans were accountable to divine law but were also endowed with reason and conscience to respond to it. He preached that sin was real and devastating, but not inevitable , explaining that revival, reform, and moral action were not only possible but necessary. This emphasis on personal responsibility, coupled with an unwavering belief in the transformative power of divine grace, made Beecher a theological bridge between the Puritan heritage of New England and the evangelical reform movements of the 19th century.

One of Beecher’s most significant sermons, “The Memory of Our Fathers” (1827), was delivered on the anniversary of the Plymouth landing. In this address, Beecher connected the legacy of the Puritans to contemporary calls for moral renewal in America. He saw the nation as a chosen vessel for divine purposes and used his pulpit to call for a return to moral rigor and religious devotion. Other key sermons, such as his “Lectures on Political Atheism and Moral Agency” (1834), addressed the relationship between religion and civil society, and “A Plea for the West” (1835) warned of the dangers of Catholic influence and secularism in the American frontier. While “A Plea for the West” contained nativist overtones, it underscored Beecher’s belief that Protestantism was integral to maintaining the moral and civic order of the United States, especially as it expanded westward. These works reflect his broader vision of Protestant evangelicalism as the cultural backbone of the republic, a view that resonated with the growing sentiment of Manifest Destiny during the antebellum era.

Beecher’s moral theology also had practical ramifications, particularly in his advocacy for social reform. His belief in the interconnectedness of individual virtue and public morality led him to take strong stances on issues such as temperance and slavery. In 1826, Beecher published Six Sermons on Intemperance, one of the most influential anti-alcohol tracts of the time. Widely reprinted, it helped shape national conversations about alcohol abuse and its social consequences. Similarly, Beecher’s stance on slavery, while not as radical as his son Henry Ward Beecher or daughter Harriet Beecher Stowe, was nonetheless firm. He condemned slavery as a moral evil and advocated for gradual emancipation, aligning with the early abolitionist sentiments that were gaining traction in the North.

Beecher’s work was not confined to the pulpit. In 1832, he became president of Lane Theological Seminary in Cincinnati, a position that placed him at the heart of national debates over slavery, westward expansion, and theological education. Lane Theological Seminary became a hotbed for anti-slavery activism, particularly among the “Lane Rebels,” a group of students who went on to become prominent abolitionists. Beecher’s leadership at Lane further cemented his role as a key figure in the broader abolitionist movement. He was not content to hold his faith as merely an academic exercise; his beliefs had practical consequences, and his activism reflected a deep commitment to social and moral reform.

Beecher’s influence extended beyond his own lifetime, largely through the work of his children, who carried forward his moral and theological legacy. His daughter, Harriet Beecher Stowe, wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which became one of the most important works in making the abolitionist movement a national cause in the North. Her novel helped humanize the plight of enslaved people and galvanized anti-slavery sentiment in the years leading up to the Civil War. His son, Henry Ward Beecher, became one of the most famous abolitionist preachers of the 19th century, using his pulpit to advocate for the end of slavery and the promotion of civil rights. Lyman Beecher’s theological and moral framework provided the foundation for their work, ensuring that his influence would resonate in the fight for emancipation and civil rights long after his death.

Throughout his life, Lyman Beecher remained a man of deep conviction, unafraid to challenge the status quo in the name of moral and religious reform. His legacy as a preacher, theologian, and social reformer is inextricably tied to the broader currents of the Second Great Awakening, which sought to transform American society through religious revival, moral action, and social activism. Beecher’s passionate advocacy for abolition, his moral vision for the nation, and his deep commitment to reform continue to resonate in American history as an example of how religious conviction can shape the course of a nation.

For further reading:

1. Hankins, Barry. The Second Great Awakening and the Transcendentalists. Greenwood, 2004.

2. Noll, Mark A. America’s God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

3. Todd, Obbie Tyler. The Beechers: America’s Most Influential Family. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2024.