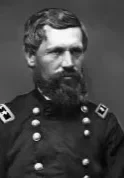

Oliver Otis Howard

November 8, 1830 - October 26, 1909

Union General in the Civil War

Union General in the Civil War

From Leeds, Maine

Served in United States

Affiliation: Baptist

"The rights of the freedman, which are not yet secured to him, are the direct reverse of the wrongs committed against him. I never could conceive how a man could become a better laborer by being made to carry an over heavy and wearisome burden which in no way facilitates his work. I never could detect the shadow of a reason why the color of the skin should impair the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness."

Oliver Otis Howard was one of the most enigmatic figures of the Civil War, yet he was also one of its most profoundly devout Christian leaders. His faith was not a private matter but an integral part of his decision-making, leadership, and postwar efforts. From the battlefields to Reconstruction, Howard’s legacy was shaped by his deep conviction that God’s providence guided his life and work. To understand the significance of his faith, it is essential to examine his life before, during, and after the war, as well as the way his beliefs informed his actions.

Born in 1830 in Leeds, Maine, Howard was raised in a devout Baptist family. He attended Bowdoin College, where he developed a strong interest in theology alongside his academic studies. Later, at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, he wrestled with the tension between a military career and his growing religious convictions.

Howard’s meteoric rise in the Union Army began when he was appointed colonel of the 3rd Maine Infantry, quickly advancing to brigadier general after the Battle of First Bull Run. His leadership of a brigade composed largely of German immigrants marked the beginning of his reputation as a commander willing to lead diverse forces. He served with distinction in the Army of the Potomac under General George B. McClellan, but it was at the Battle of Fair Oaks in 1862 that his faith was tested in a profound way. During the battle, Howard was severely wounded and lost his right arm.

Rather than retreat from service, Howard’s faith propelled him forward. He continued leading troops, inspiring soldiers with his steadfastness. His reliance on prayer and scripture became legendary among his men, earning him the moniker “The Christian General.” His presence was felt in some of the most critical battles of the war, including Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. At Chancellorsville, his corps suffered a devastating attack by Stonewall Jackson’s forces, yet Howard remained composed, believing the outcome was in God’s hands. “We must trust in Him, even in defeat,” he reportedly told his officers after the battle.

When Howard was reassigned to the western theater, he played a significant role in the Chattanooga campaign and later joined General William T. Sherman in his infamous “March to the Sea.” His faith did not waver even amid the brutal realities of war. Despite the destruction caused by Sherman’s campaign, Howard often ensured that civilian populations were protected as much as possible, in line with his belief that Christian duty extended beyond the battlefield.

With the war’s conclusion, Howard’s commitment to his faith found its greatest expression in his leadership of the Freedmen’s Bureau. As Commissioner, he was tasked with assisting formerly enslaved individuals as they transitioned to freedom. Education was one of his primary concerns. Under his leadership, thousands of schools were established across the South, including Howard University, which still bears his name.

The work of the Freedmen’s Bureau was fraught with challenges, as resistance from white Southerners and political opposition in Washington made its efforts difficult to sustain. Howard, however, viewed his mission in religious terms.

Despite his best efforts, Howard’s tenure at the Bureau was met with controversy. Some critics accused him of being overly idealistic, while others saw his Christian paternalism as patronizing. Nevertheless, his belief in racial equality, informed by his faith, remained unwavering. Even after the Bureau was dissolved, Howard continued his advocacy for African American education and missionary work.

Howard’s faith was not confined to prayer or personal devotion; it was an active force that dictated the course of his life. He saw his military service as part of a divine plan, believing that God placed him in moments of crisis for a higher purpose. Unlike many officers of his time, Howard was unafraid to make decisions that aligned with his religious convictions, even when they put him at odds with peers or political leaders. He carried his Bible with him in camp and consulted scripture before major decisions, convinced that God’s guidance was paramount. His faith drove him to fight for justice beyond the battlefield, seeing the moral imperative of Reconstruction as equal to the military struggles of the war itself. To Howard, his faith was inseparable from his duty—both as a soldier and as a servant of a higher cause.

Howard’s unwavering commitment to his beliefs often made him a polarizing figure. Some contemporaries admired his steadfastness, while others viewed his piety as excessive. A fellow officer once remarked, “Howard would have made a better preacher than a general.” But Howard himself saw no contradiction between his roles as a soldier and a man of faith.

By the time of his death in 1909, Howard’s legacy was firmly established as a man whose faith shaped his actions in war and peace alike. His life serves as a testament to the ways in which deep religious conviction can inspire leadership, perseverance, and a commitment to justice. For Howard, faith was not merely a personal comfort—it was the guiding force of his extraordinary life.

For further reading:

1. Carpenter, John. Sword and Olive Branch: Oliver Otis Howard, (Fordham, NY: Fordham University Press, 1999).

2. Howard, Oliver Otis Howard, Autobiography of Oliver Otis Howard, major general , United States army : volume 1.

3. Myers, Barton A. “O. O. Howard and the Freedmen’s Bureau”.

4. Consider downloading and reading Oliver Otis Howard’s autobiography.