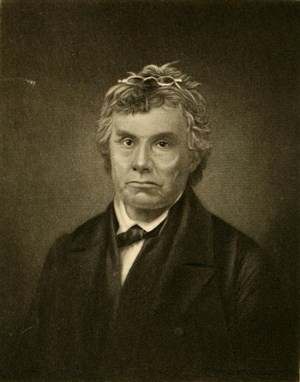

Peter Cartwright

September 1, 1785 - September 25, 1872

Preacher and Evangelist

Preacher and Evangelist

From Amherst County, Virginia

Served in Illinois

Affiliation: Methodist

“What a sad account will many preachers have to give in the day of judgment, who have preached a free salvation to listening thousands, while their poor degraded slaves are deprived of many of the blessings of life, and privileges of civil and religious liberty! These preachers must and do know that slavery is at war with the attributes and perfections of God, who will never punish the innocent or let the guilty go free.”

Peter Cartwright was a man forged by the frontier, a plainspoken, passionate, and fiercely convicted man. Born on September 1, 1785, in Amherst County, Virginia, Cartwright came of age in the raw borderland of Logan County, Kentucky, where his family settled amid the hard edges of early American expansion. It was here, in the rough and fervent atmosphere of the Great Revival, that Cartwright experienced a profound conversion during his teenage years. That moment was dramatic, emotional, and deeply personal, shaped the rest of his life. At just 18, he joined the ranks of Methodist circuit riders, launching a ministry that would stretch across fifty years and thousands of miles of untamed territory.

Cartwright quickly gained a reputation as a preacher who pulled no punches. His sermons, often delivered under open skies at camp meetings, stirred crowds with their fervor and frankness. He preached as if the stakes were life and death because to him, they were. In his autobiography, he recalls the spiritual epiphany that marked his conversion: “It appeared to me that I heard a voice from heaven, saying, ‘Peter, look at me.’ A feeling of relief flashed over me as quick as an electric shock.” Such moments, vivid and electrifying, weren’t rare at the revival meetings he led. He believed in emotional engagement as a path to salvation, and the rough-and-tumble frontier responded in kind.

Cartwright’s faith was not confined to the pulpit. He saw Christianity as a call to moral action, and his religious convictions led him to take a bold stand against slavery. At a time when many of his fellow ministers looked the other way or used Scripture to defend the practice, Cartwright denounced it without apology. In one striking passage from his autobiography, he wrote, “What a sad account will many preachers have to give in the day of judgment, who have preached a free salvation to listening thousands, while their poor degraded slaves are deprived of many of the blessings of life.” This sense of moral clarity extended beyond the church. In 1846, he even ran for Congress against Abraham Lincoln. He lost the election but won a place in history for his fearless advocacy.

Though never trained in theology, Cartwright’s influence rested not in academic argument but in lived conviction. He spoke plainly, drawing from personal experience rather than doctrine, and his stories carried a raw authenticity. One of the most famous comes from an 1818 sermon in Nashville, where General Andrew Jackson sat in the audience. Cartwright, never one to mince words, thundered from the pulpit, “If he don’t get his soul converted, God will damn his soul as quick as He will a Guinea [slave].” It was a shocking moment—brash, unfiltered, and entirely in character. Jackson reportedly admired the preacher’s boldness.

What makes Cartwright so fascinating is how much of his legacy rests on his own telling of it. The Autobiography of Peter Cartwright, published in 1856, remains the primary record of his life. Unlike other religious leaders of his time who left behind detailed sermons, letters, and institutional records, Cartwright’s story is almost entirely self-authored. This presents certain challenges for historians. His tales are colorful and sometimes improbable, and it’s not always easy to separate fact from embellishment. Yet the book is an irreplaceable resource, offering an unvarnished look at a form of Christianity that flourished in the rough terrain of the American heartland. In its pages, we hear not only the voice of one preacher but the cadence of a movement.

In Cartwright, we find the very spirit of the Second Great Awakening distilled to its essence. He embodied the revivalist’s fervor, the circuit rider’s stamina, and the reformer’s moral fire. His faith was democratic in its reach, which he offered freely to the poor farmer, the weary traveler, the skeptical townsman, and insistent in its demands. Religion, for Cartwright, was never passive. It called for action, for change, for transformation. His belief in free will, salvation, and sanctification found an eager audience in a nation on the move, grappling with its identity and its future.

Unlike some religious figures who are defined by their ecclesiastical offices or liturgical habits, Cartwright lived his faith out loud and on the road. The frontier was his sanctuary, the pulpit his saddlebag. What we do know is this: his life bore witness to a kind of public faith which was unvarnished, unapologetic, and deeply influential. In an age of religious awakening, he helped awaken a nation. Despite his fiery reputation, Peter Cartwright also represented the pastoral heart of the frontier church. His dedication to circuit riding, often preaching multiple times a day, traveling by horseback in harsh conditions, and ministering to isolated communities, revealed a deep commitment to the spiritual welfare of ordinary people. Cartwright baptized many, presided over countless conversions, and provided stability and moral guidance in communities often marked by transience and lawlessness. Though often remembered for his confrontational style, he was equally defined by his pastoral care and the consistency of his witness over decades of ministry. In this way, Cartwright exemplified how revivalist Christianity not only stirred souls but also planted churches, shaped communities, and offered a cohesive spiritual framework to a rapidly expanding and changing nation.

In the end, Peter Cartwright’s story is about more than one man’s ministry. It is a chapter in the larger tale of American religious life which was gritty, spontaneous, and shaped by the demands of a growing republic. He may not have left a library of theological treatises, but he left a legacy of spiritual fervor and moral clarity that still echoes today.

For further reading:

1. Breen, T.H. The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

2. Cartwright, Peter. Autobiography of Peter Cartwright, the backwoods preacher. editeds by Strickland, W. P Cincinnati, L. Swormstedt & A. Poe for the Methodist Episcopal church, 1859. Pdf.

3. Manning, Chana. God’s New Israel: Religious Interpretations of American Destiny. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.