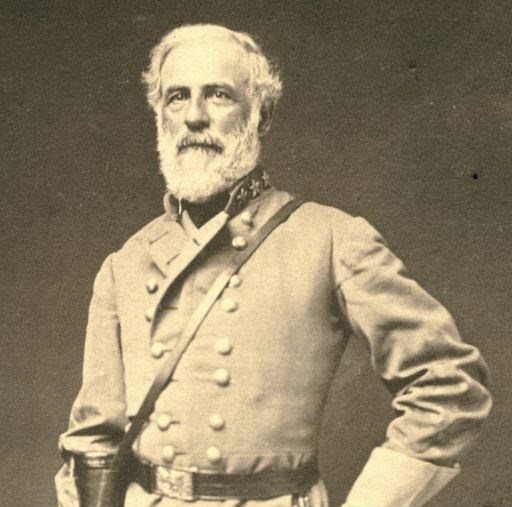

Robert E. Lee

January 19, 1807 - October 12, 1870

Confederate General during the American Civil War

Confederate General during the American Civil War

From Stratford Hall, Westmoreland County, Virginia

Served in Southern United States

Affiliation: Episcopal

“My experiences of men has neither disposed me to think worse of them nor be indisposed to serve them: nor, in spite of failures which I lament, of errors which I now see and acknowledge, or the present aspect of affairs, do I despair of the future. The truth is this: The march of Providence is so slow and our desires so impatient; the work of progress so immense and our means of aiding it so feeble; the life of humanity is so long, that of the individual so brief, that we often see only the ebb of the advancing wave and are thus discouraged. It is history that teaches us to hope."

Robert E. Lee was one of the most widely recognized and respected figures of the American Civil War. A proud son of Virginia, he devoted his life to the service of his home state, even at the cost of breaking ties with the United States Army, where he had served with distinction for over three decades. When war loomed, he declined an offer to command Union forces, instead choosing to lead the Army of Northern Virginia in defense of the fledgling Confederate States of America. Yet beyond his military prowess, Lee was deeply committed to his Christian faith, a defining aspect of his character that shaped his actions both in war and in peace.

Lee’s faith was instilled in him from an early age. Raised in an Episcopalian household, he maintained a lifelong devotion to the teachings of Christ. He read scripture daily, prayed fervently, and sought to live by Christian principles, even in the most tumultuous of times. This guiding principle influenced both his leadership style and his personal conduct, earning him the reputation of a true Southern gentleman.

Before the Civil War, Lee distinguished himself as a soldier and engineer, serving with valor in the Mexican-American War. There, he fought alongside men who would later become both his allies and adversaries, including Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson and Ulysses S. Grant. His military genius was evident early, yet he viewed warfare with a sense of Christian duty rather than personal ambition. He saw his role as a soldier as a service to a higher cause, believing that “duty is the most sublime word in our language.”

When the Civil War erupted, Lee’s decision to align with Virginia was agonizing. He believed in the Union but could not bear to take up arms against his home. “With all my devotion to the Union, and the feeling of loyalty and duty as an American citizen, I have not been able to make up my mind to raise my hand against my relatives, my children, my home,” he explained. His choice was not simply political but spiritual; he saw himself as bound by divine providence to defend his homeland. Once committed, he approached the war with the same sense of moral duty that had governed his entire life.

As the leader of the Army of Northern Virginia, Lee relied on his faith to sustain him through the tribulations of war. He carried a pocket Bible and was often seen in prayer. His letters to his family reveal a man who believed that ultimate victory lay not in military triumph but in God’s will.

Lee’s faith also shaped his views on slavery, though they were complex and contradictory. He inherited slaves from his wife’s family and managed their estate for several years. While he described slavery as “a moral and political evil,” he also believed that its eradication should come through divine means rather than human intervention. Lee’s paternalistic view of slavery was common among Southern Christians of his era but placed him in direct contrast with abolitionist interpretations of the Gospel.

Despite his role in defending the Confederacy, Lee’s personal conduct during the war reflected his Christian convictions. He treated prisoners with dignity, sought to minimize suffering, and encouraged his men to maintain their moral integrity. Following the defeat at Gettysburg—a turning point often considered his greatest military misstep—Lee was not despondent but resigned. Lee assured his officers that God’s will, not human strategy, would dictate the course of events.

As the war dragged on, Lee saw the Confederacy’s decline as both a military and spiritual reckoning. When Richmond fell in April 1865, he urged his soldiers to surrender with honor. At Appomattox, he met with Ulysses S. Grant, himself a man of deep conviction, and accepted defeat with humility. To his troops, he issued a final order: “You will take with you the satisfaction that proceeds from the consciousness of duty faithfully performed.”

In the aftermath of the war, Lee’s commitment to Christian principles became even more evident. He opposed guerrilla resistance, urging Southerners to reconcile with the Union. He accepted the presidency of Washington College (now Washington and Lee University), where he sought to educate young men in both knowledge and character.

Lee’s death in 1870 marked the beginning of his transformation into an almost mythic figure. The Lost Cause movement elevated him to near-sainthood, portraying him as the ultimate Southern gentleman—noble, virtuous, and devoted to duty. Yet amidst this myth-making, the core of Lee’s character remained: a man whose faith was the bedrock of his life. As historian Thomas L. Connelly wrote, Lee became The Marble Man, revered not just for his military acumen but for the steadfast moral compass he exhibited through war and peace alike.

While modern perspectives on Lee are often divided, his deep and abiding Christian faith remains a crucial part of understanding him. His life was shaped by his belief in providence, his sense of duty, and his efforts to align his actions with his spiritual convictions. Whether on the battlefield, in the quiet of his study, or in the chapel of Washington College, Lee was, above all, a man of faith—a faith that guided him in triumph and in defeat, in war and in reconciliation, until his final breath.

For further reading:

1. Connelly, Thomas. The Marble Man: Robert E. Lee and His Image in American Society. (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1978).

2. Nolan, Alan T. Lee Considered: General Robert E. Lee and Civil War History. (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1991).