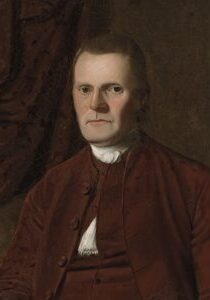

Roger Sherman

April 19, 1721 - July 23, 1793

Founding Father of the United States

Founding Father of the United States

From Newton, Massachusetts

Served in New Haven, Connecticut

Affiliation: Congregational

“I believe that there is one only living and tru God, existing in three persons, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, the same in substance, equal in power and glory. That the Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments are a revelation from God, and a complete rule to direct us how we may glorify and enjoy Him.”

In the modern world, signing one’s name on a document might involve a fiduciary commitment, or communicate a covenantal agreement, or denote the acquisition of property at a cost to the signee. A person’s signature represents his promise to fulfill the obligations of the agreement. Rarely does one’s name on a piece of paper place that person’s life in danger. It also does not assist in setting in motion a transformative government that will determine and/or affect future, world history in such a significant manner.

In all of history, only one man’s pen threatened his own life with termination and at the same time set in motion or continued events of a high magnitude. Roger Sherman signed four of the United States’ most critical documents. He signed the Articles of Association which declared a colony-wide boycott of British goods. He also added his name to the Declaration of Independence, which stated autonomy from the world’s superpower at the time. If he had been captured by the British, he surely would have been hanged. As well, Mr. Sherman signed the Articles of Confederation which provided an infant nation with its first operating political structure. Finally, the New Englander endorsed the United States Constitution, which is the country’s enduring set of political principles and operations. He is the only colonist who signed all four documents.

Roger Sherman’s ancestors sailed to America in about 1636 and settled in New England. His father, John Sherman, married Martha Palmer the next year, and the couple established their home in Watertown, Massachusetts. Two generations later, William Sherman wedded Mehetabel Wellington. Roger, the third oldest of their seven children, was born on April 19, 1721. With his family, young Roger grew up in Stoughton, Massachusetts. Father Sherman was a farmer who worked the land off a main road near the small town. He supplemented his income with cobbler work. The Sherman children’s upbringing was full of pious devotion to the Almighty and assistance on the farm. This left little time for play or entertainment. On Sundays, the family dedicated their time solely to the things of God and His church.

Master Roger’s education was most basic. During this time period in his area, education had deteriorated significantly. He did not attend a formal school until he was 12 or 13 years of age when the first schoolhouse in Stoughton was built in 1734. Its academic rigor was quite less compared to schools attended by many of the other signers of the Declaration of Independence. In addition to reading, writing, and arithmetic, there was also Christian catechism. It is believed his education was greatly augmented by his consumption of the knowledge found in his father’s library and the tutoring of Harvard-trained Rev. Samuel Danbar. From the minister, young Roger learned mathematics, science, literature, and philosophy.

At the outset of his adulthood, Roger Sherman’s father died in 1741. Immediate stress was foisted upon the 19-year-old as executor of his father’s estate. He was challenged with debt management and care for his mother and his younger siblings. In 1743, he was selected as surveyor for New Haven County. A few years later, he happened upon the profession of law when he was asked by a neighbor to inquire of a lawyer about a deceased person’s affairs the neighbor was managing. In preparation for the conversation, Mr. Sherman wrote a personal memorandum about the matter. At the end of speaking with the lawyer, the man asked Mr. Sherman for his notes. After reviewing the orderliness and thoroughness of his accounting of the situation, the lawyer, impressed by what he had read, encouraged Mr. Sherman to pursue the career of an attorney.

Roger Sherman studied the law in the subsequent years. He also set up with his brother, William, a general store in New Milford in 1750. This business, plus his surveying work, provided a steady income of significance. As a result, he began investing in land. This yielded very profitable returns. After completing his studies of the law, he asked the lawyers of the Connecticut bar to be admitted to the body and was accepted. This was an impressive feat in light of the high standards held by the bar. In February 1754, he was permitted to practice law in Litchfield County, Connecticut. Business blossomed over the next year or so with 125 cases of his being heard in the Litchfield and Fairfield county courts.

Roger Sherman’s quality reputation soon became well-known more broadly. In October 1754, he was voted to be a selectman in New Milford. He was also chosen to be the justice of the peace for Litchfield County and a member of the General Assembly. He served as New Milford’s representative until 1758 and then served again from 1760-61. Mr. Sherman also served as treasurer for his church during a building capital campaign in addition to other roles.

Tragedy struck Sherman’s life in October 1760. His wife of 11 years, Elizabeth Hartwell Sherman, died following the birth of their youngest child. The two of them had seven children together. Three of them died in infancy. A short time afterward he moved himself and his children to New Haven. It is presumed the memory of his and his wife’s time together in New Milford was too much to bear. Three years later on May 12, he wedded Rebecca Prescott. His second wife bore eight children. One child died in infancy.

Mr. Sherman continued his public service to the people of New Haven. In the fall of 1764, he was elected deputy to the General Assembly for his town. Then in 1765, he was selected as justice of the peace and justice of the county quorum. He became a judge on the state Superior Court. All the while, he continued to operate the store until 1772 when he gave his son, William, the reins. He served his community, state, and future country from this point forward.

On March 22, 1765, Parliament passed the Stamp Act. This law required colonists to pay a tax on all commercial and legal paper, newspapers, cards, pamphlets, almanacs, and dice. Once a colonist paid his tax on the item, a stamp was placed on it to indicate the tax had been paid. The British government enacted the tax in order to recoup from the colonists the money it had spent protecting them and English interests in the French and Indian War. Britain had incurred significant debt fighting the French for seven years. The tax enraged the colonists who argued they had no representation in Parliament to voice their opposition, let alone vote against the act.

In response, the Massachusetts Assembly proposed a colonial congress be convened to discuss how the colonies should address the issue. Connecticut sent Roger Sherman and others to the congress. The congress passed a resolution condemning the tax and petitioned the crown and Parliament that the colonies had the right to determine their own tax system. The body also resolved no business would be conducted using stamped items during that winter. England felt the economic pain of the colonists’ action and Parliament capitulated under the circumstances on March 18, 1766, with a repeal of the act. The MPs had the last word, however. On the same day, they passed the Declaratory Act which stated the British Parliament had the legal right to legislate in all matters concerning the colonies. In addition, the tax on tea persisted and led to the Boston Tea Party. The English responded with the Intolerable Acts among which the Boston harbor was closed until the colonists paid for the tea that was lost. As well, Parliament made most positions in the Massachusetts government appointive rather than elective. The fissures between the two parties were widening. Even though all hope was not lost, it was becoming noticeably dim.

At the initiative of the Virginia Burgesses, a congress was convened in May of 1774 in Philadelphia. During this term of the First Continental Congress, Delegate Roger Sherman and other delegates from the colonies, save Georgia, responded to the Intolerable Acts with the Articles of Association which declared a boycott against British goods. The Congress also petitioned the king one final time to reconcile their differences. Their Olive Branch Petition was rejected. Both of these documents were signed by Mr. Sherman.

In April 1775, General Gage received orders from London and set upon Concord to seize the militias’ arms. The king did not foresee nor understand the American spirit he stirred up. King George III and the British greatly underestimated the grit of their subjects who lived over 3,500 miles away. Their representatives, including Roger Sherman, gathered in Philadelphia to determine a path forward. They voted on July 2, 1776, that independence from British rule was their only option.

“… it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.”

The Declaration, based on Richard Henry Lee’s resolution for colonial independence, was signed by Roger Sherman and most of the other signatories on August 2. Sherman’s depth of service at the state and colonial levels took a significant toll on his health. At one point, he asked Connecticut Governor Trumbull for a reprieve from state duties. He continued to represent Connecticut in Philadelphia until 1781.

Upon the declaration that “these states are and of right out to be free” from British rule, the infant nation needed an operating structure. Roger Sherman and 12 other delegates set about to create a document detailing the democratic republic. The Articles of Confederation were adopted in November 1777. Though not included in this founding document, Mr. Sherman suggested the rough framework for the U.S. government’s bicameral structure which was included in the United States Constitution.

Roger Sherman worked tirelessly for the United States in the Continental Congress. As a Board of War member, he visited the front lines to meet with General George Washington and other military leaders on multiple occasions. He served on the finance committee and the Board of Treasury. He also assisted in purchasing supplies for the army, managing relations with the Native Americans, and overseeing the post office. Every year, he served on one or more committees. Overall, he served in Congress from 1774 to 1782. Mr. Sherman returned in 1783 and his time ended in Philadelphia in 1784.

Back home, Mr. Sherman sat on the Governor’s Council, served on the Connecticut Superior Court, and led New Haven as its mayor. When a convention was called to revise the Articles of Confederation in May 1787, he returned to Philadelphia to assist his fellow founding fathers in hammering out a constitution that appropriated power to the federal government in a measured manner. He spoke often on the convention floor addressing the assembly 138 times. Three months later, the 41 delegates completed their work and signed the United States Constitution.

In his last years, Roger Sherman never flagged in his public service. He served in the House of Representatives (1789–91) and later in the Senate (1791-93). He partnered with Alexander Hamilton and his efforts for the federal government to assume the states’ debts, establish a national bank, and levy tariffs on British goods for the protection of American-produced goods.

It is recorded Mr. Sherman’s health suddenly declined due to typhoid fever. Before this, it seemed he would enjoy robustness of life into his very senior years. It was not to be. He died on July 23, 1793.

Roger Sherman’s character and reputation were of the most admirable quality. Thomas Jefferson said of him, “That is Mr. Sherman of Connecticut, a man who never said a foolish thing in his life.” He is also praised for a consistent, devout life.

“To the above excellent traits in the character of Mr. Sherman, it may be added, that he was eminently a pious man. He was long a professor of religion, and one of its brightest ornaments. Nor was his religion that which appeared only on occasions. It was with him a principle and a habit. It appeared in the closet, in the family, on the bench, and in the senate house. Few men had a higher reverence for the bible; few men studied it with deeper attention; few were more intimately acquainted with the doctrines of the gospel, and the metaphysical controversies of the day.”

Roger Sherman lived to be 72 years of age.