"Be not too curious of Good and Evil; Seek not to count the future waves of Time; But be ye satisfied that you have light, Enough to take your step and find your foothold."

In 1931, T.S. Eliot wrote in his essay, “Thoughts After Lambeth,” “The World is trying the experiment of attempting to form a civilized but non-Christian mentality. The experiment will fail; but we must be very patient in awaiting its collapse; meanwhile redeeming the time: so that the Faith may be preserved alive through the dark ages before us.”

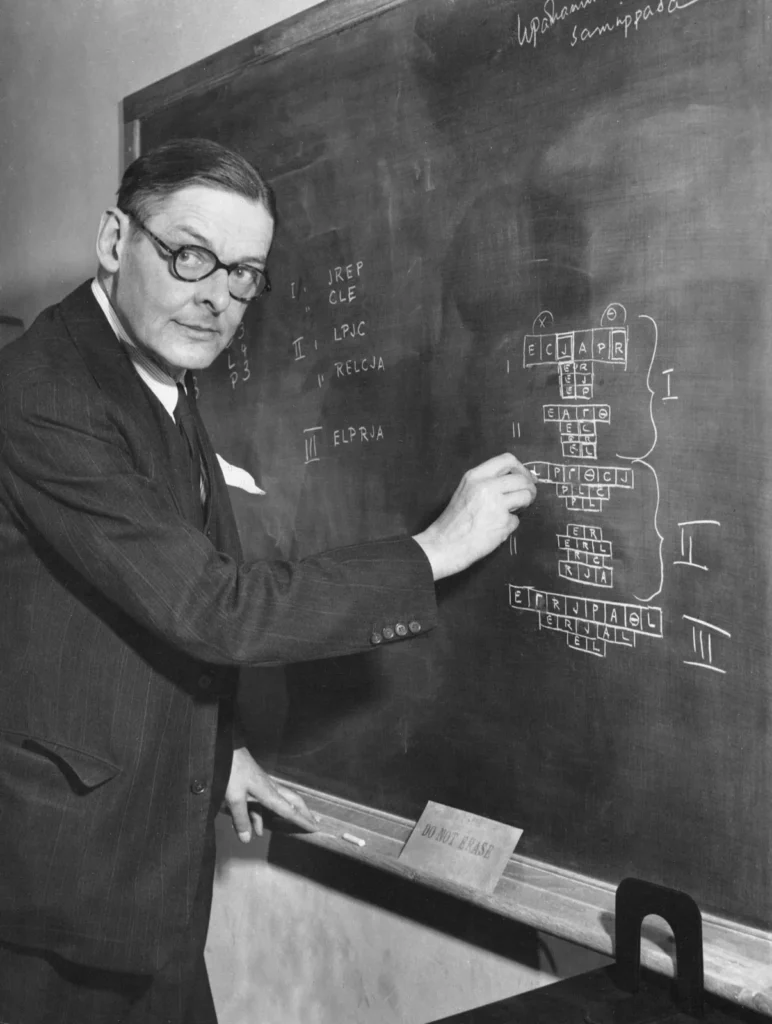

Eliot’s insight into the perseverant perniciousness of modernity is clairvoyant. The Nobel Poet Laureate had been educated in the most elite institutions and he was living in one of the world’s most cosmopolitan cities surrounded by friends and associates who were consumed by modernistic thought. After converting to Christianity, the veil shrouding the vainness of modernity’s promises fell and he recognized its futility. His allusion to the Holy Scriptures and his encouragement to persevere were anathema in the literary world of his day. But the American cum Brit understood, from experience, the deceitful lies the current age was propagating.

Thomas Stearns Eliot was born in the “gateway to the west,” St. Louis, Missouri on September 26, 1888. His family, with deep New England roots, had moved west during his grandfather’s lifetime. William Greenleaf Eliot, a graduate of Harvard Divinity School, moved west in 1830 and established a Unitarian church in Mississippi. In time, the family moved to St. Louis and remained there for three generations. Some of T.S. Eliot’s New England ancestral heritage includes John Quincy Adams and the author, Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Eliot’s educational resumé is prestigious. He attended two of the country’s finest private schools in St. Louis and Massachusetts. His undergraduate and graduate years were spent at Harvard University, University of Paris-Sorbonne, and Merton College at Oxford University. When he arrived at Oxford in 1914, due to a fellowship from the Harvard philosophy department, he planned to study Aristotle and write his dissertation for the next 12 months. Two significant events changed not only his plans, but also his career trajectory.

In May 1915, T.S. Eliot met the daughter of an artist, Vivienne Haigh Wood. Dance was one of the things they initially bonded over. In light of Miss Wood’s love of dance, Eliot impressed her by knowing the latest dance craze, the Grizzly Bear. From May until June, Eliot swooned over her and was taken by her quirkiness. Without the support of their parents, on June 25, 1915, they married at a local Registry Office in North London.

Mr. Eliot was not overzealous to become a poet, but his soon-to-be bride made it her mission to see his works published. At this point in time, only a few of his poems had been published and that was in limited form in the student publication, the Harvard Advocate. Vivienne was adamant Eliot press forward with his poetry. His good friend and fellow poet, Ezra Pound, seconded Vivienne’s mission. After reading one of Eliot’s poems, “The Love Song of J. Prufrock,” he wrote to Poetry’s editor, Harriet Monroe, “He has actually trained himself and modernized himself on his own.” The highly-regarded literary journal published the piece the same month he wedded Vivienne. Acclaim and success followed as a collection of his poems along with Prufrock were published in 1917. A second volume of his poems were published by Virginia and Leonard Woolf in 1918. The adulation catapulted him to the top of London’s literati, which held court over the global literary world at the time.

Regarding “The Love Song of J. Prufrock” specifically, T.S. Eliot detailed the modern man in a state of self-doubt. Despite having much formal education, it had not assisted him in overcoming an unfulfilled inner life. And his romantic life had become a tangled mess of apprehension and regret. Eliot remarked that the poem was somewhat autobiographical. He wrote the poem during a five-year search for a belief system with cultural, intellectual, and spiritual robustness. His family’s religion, Unitarianism, had provided none of this. The heterodox form of Christianity, which denies multiple doctrines of the Christian faith including the deity of Christ and the Trinity, “cast a pessimistic shadow on Eliot’s earlier poems.”

“Prufrock” is considered the end of the first period of his life as a poet. The poem with others of T.S. Eliot’s were published in 1917 in a volume entitled, “Prufrock and Other Observations.” It is argued this publication marked the maturation point of the 20th century poetic revolution. He and Ezra Pound were determined to “reform poetic diction” and Eliot focused on new verse rhythms that were closer to the patterns of contemporary speech.

Despite the accolades and being published, T.S. Eliot was struggling. Upon the publication of “Prufrock,” he was ecstatic telling his brother via letter, “I feel more alive than I ever have before.” But four years later (1919), his disposition has changed greatly. Again writing to his brother, “It is like being always on dress parade—one can never relax. It is a great strain. And [English] society is in a way much harder, not gentler. …They seek your company because they expect something particular from you, and if they don’t get it, they drop you.”

Not only was the place of his living difficult, but also the state of his living was tumultuously difficult. Mr. Eliot and Mrs. Eliot immediately discovered their incompatibility. Vivienne was plagued with physical hardship and mental illness, which worsened during their marriage. At age 11, she had endured tuberculosis of the arm. After this, she would suffer from continuing instances of headaches, backaches, stomach aches, and more. Her illnesses were treated with a variety of drugs. Some of which contained morphine. This began her dependency on drugs. Eliot knew none of this prior to marriage.

In addition, Eliot was sick now and again to the point of being bed-ridden, at times. These issues, plus his meager wage as a banker, stripped all newlywed joy from their souls. “Financial desperation, overwork, housing problems, neglect, irritability, bickering (some of their intimates would resolve never again to spend an evening together with the two of them)” created the barrenness Eliot would later detail in one of his most regarded works.

“I think that all I wanted of Vivienne was a flirtation or mild affair: I was too shy and unpracticed to achieve either with anybody. I believe that I came to persuade myself that I was in love with her simply because I wanted to burn my boats and commit myself to staying in England. And she persuaded herself (also under the influence of Pound) that she would save the poet by keeping him in England. To her, the marriage brought no happiness. . . . To me, it brought the state of mind out of which came ‘The Waste Land.’”

The work is the culmination of T.S. Eliot’s second period. Published in 1922, one scholar points to the new language used by him culled from everyday life. (For example, words such as record, motor cars, food in tins). Another points to Eliot’s critique of technological advancements being dehumanizing forces along with other recent historical events, e.g. World War I. The poem’s disjointed form mirrored the current chaos experienced by Eliot and the chaos he sees in the post-war world. There is a yearning, a search for redemption. But nothing is found in the spiritually desolate culture.

Due to his family’s Unitarian roots, Eliot was constantly searching for spiritual principles to live by and to answer life’s questions with. Duty, a key part of his childhood, was not something he left when he left Unitarianism. He searched for its anchor in eastern religions and mysticism. At a crucial point in time, he read his friend’s essay entitled, “A Free Man’s Worship.” In this work, Bertrand Russell advocated man must worship man. Eliot was not impressed. Russell’ argument for this assertion was not persuasive. Eliot began moving toward Christianity.

T.S. Eliot’s turn to Christianity was not a Damascus Road occurrence, which he was skeptical of. It was a progression. He was wanting more than a vague mysticism and more than a self-sufficient moralism. Several stories illustrate this. During a visit to Rome in 1926, he fell to his knees, in a seeming sign of reverence, in front of Michelangelo’s Pieta. Another was his attendance of early morning communion that came to light when he stayed with his friend, Virginia Woolf. In 1927, he formally converted to Christianity and was baptized in a church in the village of Finstock, located in the Cotswolds. He became a lifelong Churchwarden in his parish church, St. Stephen, an Anglo-Catholic church in the Church of England. Eliot chose this wing of the Church of England because he felt strongly about being a part of the universal Catholic Church.

Also, following his conversion, T.S. Eliot began speaking publicly against the amoral philosophy being propagated by thought leaders of his day, including his once friend Bertrand Russell. Speaking of friends, most were appalled by Eliot’s decision to convert, especially Virginia Woolf. She predicted Eliot would “drop his Christianity with his wife, as one might empty the fishbones after the herring.” Despite such sentiments (pertaining to his faith, not his wife) echoed by others and even verbal attacks, he remained on good terms with those who disagreed with his conversion. In a way, he was pleased Christianity had been relegated to the outskirts of acceptance in English society. He viewed it as a positive that it was no longer a desired component of one’s social resumé.

Christianity’s impact upon Eliot’s poetry is arguably first seen in 1930 with the publication of “Ash Wednesday.” The work speaks of turning one’s back, repentance, on the world and its system. Eliot did not fancy it being referenced as a religious poem, but the theme of bold renunciation is difficult not to see. He preferred to describe the work portraying a stage in a person’s life:

Because I do not hope to turn again

Because I do not hope

Because I do not hope to turn

Desiring this man’s gift and that man’s scope

I no longer strive to strive towards such things

Two years later, in 1932, T.S. Eliot and Vivienne separated. As mentioned earlier, the union had been fraying since its beginning. And yet, they had accomplished much together. She and Ezra Pound had recognized the poetic diamond inside a man in need of some strong encouragement. “Of course he has had me to shove him – I supply the motive power, and I do shove,” she declared at one point.

Despite their health struggles and the marital strife, the two collaborated successfully during their marriage. Eliot greatly valued and needed his wife’s input regarding his writings. On one occasion, he remarked, “[Vivienne] has had to do so much thinking for me [of late].” At times, her edits were noticeable improvements when contrasted with his. “A Game of Chess” is one such example: His “No, ma’am, you needn’t look old-fashioned at me” was replaced by hers, “If you don’t like it, you can get on with it.” In 1922, Vivienne helped Eliot launch what would become one the most prestigious literary journals of the day, The Criterion. She also was a significant contributor for almost a year and a half. Eliot viewed her as invaluable in the publishing process and remarked to Bertrand Russell, “She writes extremely well […] And I can never escape from the spell of her persuasive (even coercive) gift of argument.” Her assistance lasted until 1925.

When the tensions, stress, and unbearableness of their marriage are contrasted with this aspect of their lives, their marital bond is truly enigmatic. Along with great division there was also great symbiosis. “They wrote letters on each other’s behalf, shared manuscripts, and corrected each other’s work.” And yet, the fabric of their union was thread-bare and no amount of shared endeavor could rescue it from its pending demise. Their troubles weighed on the other quite heavily, and separation finally came in 1933.

At this point, Eliot turned his back on her and never saw her again. She sought to connect with him by showing up at some of his public events, but he continued to avoid interacting with her. He was not even present when she admitted to a psychiatric facility by her brother, Maurice Haigh Wood. There is no indication he ever visited her. In a peculiar turn of events, her brother returned after spending several years abroad and found she had returned to a state of mental stability. Vivienne died suddenly in 1947.

A few years before his wife’s death, T.S. Eliot published a collection of poems entitled, “Four Quartets,” in 1943. The “quartets” (each poem is structured with five sections imitating a musical quartet’s form) were initially published separately. The first, “Burnt Norton,” was published in 1936. The two, middle poems were published during the Blitz, “East Coker” (1940) and “The Dry Salvages” (1941). The final quartet was published in 1942, “Little Gidding.” When Eliot brought them together in one publication, readers recognized the unity of the four poems. There was a thread of themes and images recurring with musical rhythm across the four poems, and a final resolution that stitched them together.

Through the poems, Eliot teaches his readers, especially Christians, about man’s relationship with time, the universe, and his God. He also speaks of the great impact of Christ’s Incarnation and the restoration it will bring. Throughout his career, Eliot experimented with diction, style,and versification and, consequently, reinvigorated English poetry. His approach culminated in the Quartets, a mastery of the English language in poetic form. This led to Eliot being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1948.

Eliot’s other honors include the British Order of Merit, a 1950 Tony Award for Best Play for his play, “The Cocktail Party.” He also received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Lyndon Johnson in 1964. His children’s book, Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, was posthumously adapted as a Broadway play, which won seven Tony awards in 1983.

The person responsible for Old Possum’s Book being made into a play was Eliot’s second wife, Esmé Valerie Fletcher. At 14 years old, Miss Fletcher heard Eliot’s poem, “The Journey of the Magi,” read by Sir John Gielgud. She was captivated by the British poet and felt compelled to be his helpmeet. She steered her secretarial career in such a way to make her deep-seated conviction a reality. When she became a secretary at Faber & Faber (the publishing house where Eliot was the director for about 40 years), Miss Fletcher was assigned to administrate for him. Finally, love awoke in his breast and he asked her to marry him eight years after their first meeting. They soon married in January 1957 despite she being almost 40 years his junior. Possibly due to her youngness and the invigorating energy of love, Eliot recovered from poor health to live for another eight years.

***

T.S. Eliot was a man of courageous faith who had a gift to express that faith in an inviting and creative manner. In certain demonstrable ways, he stood against the cultural forces of his time just like his Lord stood against the religious culture of His day. Courageously, this man of letters who had been inside of polite society called from outside of it to those still members to recognize the errors of modernity and repent.

T.S. Eliot died on January 4, 1965 of emphysema. He lived to be 76 years of age.

SOURCES: T.S. Eliot.com, Poetry Foundation, Britannica, “T. S. Eliot’s Conversion from Unitarianism to Anglo–Catholicism”, “The Conversion of T.S. Eliot”, and ABC.net.au.

Selected Bibliography

Poetry

Collected Poems (1962)

The Complete Poems and Plays (1952)

Four Quartets (1943)

Burnt Norton (1941)

The Dry Salvages (1941)

East Coker (1940)

Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats (1939)

Ash Wednesday (1930)

Poems, 1909–1925 (1925)

The Waste Land (1922)

Poems (1919)

Prufrock and Other Observations (1917)

Prose

Religious Drama: Mediaeval and Modern (1954)

The Three Voices of Poetry (1954)

Poetry and Drama (1951)

Notes Towards the Definition of Culture (1949)

The Classics and The Man of Letters (1942)

The Idea of a Christian Society (1940)

Essays Ancient and Modern (1936)

Elizabethan Essays (1934)

The Use of Poetry and the Use of Criticism (1933)

After Strange Gods (1933)

John Dryden (1932)

Thoughts After Lambeth (1931)

Tradition and Experimentation in Present-Day Literature(1929)

Dante (1929)

For Lancelot Andrews (1928)

Andrew Marvell (1922)

The Sacred Wood (1920)

Drama

The Elder Statesman (1958)

The Confidential Clerk (1953)

The Cocktail Party (1950)

The Family Reunion (1939)

Murder in the Cathedral (1935)

The Rock (1934)

Sweeney Agonistes (1932)