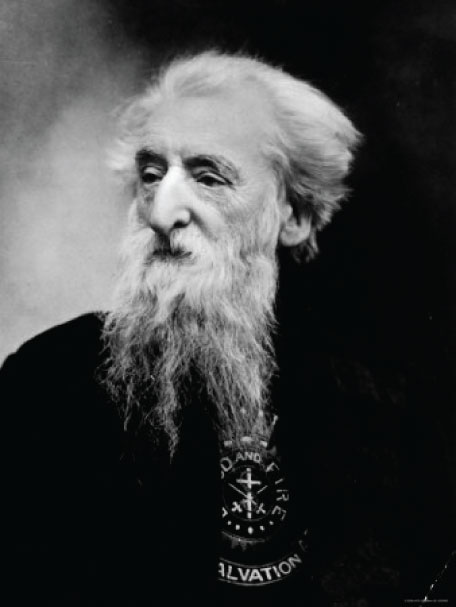

William Booth

April 10, 1829 - August 20, 1912

Founder of the Salvation Army

Founder of the Salvation Army

From Nottingham, England

Served in London, England

Affiliation: Methodist

"The chief danger of the 20th century will be religion without the Holy Spirit, Christianity without Christ, forgiveness without repentance, salvation without regeneration, politics without God, and heaven without hell."

William Booth was a preacher, evangelist, and writer who was unwilling to ignore suffering. The founder of the Salvation Army, Booth harnessed the moral urgency of the Christian gospel and organized it into a disciplined, global force for good. His life, shaped by the poverty of his youth and animated by the Christian faith of his adulthood, left a legacy that redefined how churches could engage with social problems.

Born in Nottingham, England in 1829, Booth’s early years were marked by hardship. His father was a speculative businessman whose finances collapsed, leaving the family in difficult circumstances. At the age of 13, Booth was apprenticed to a pawnbroker. It was grueling work, but in that setting he began to notice not just material poverty, but the spiritual destitution of the people around him. The experience planted a seed that would later grow into his life’s calling.

Booth experienced a religious conversion in his teenage years and soon affiliated with the Methodist Church. He began preaching in small chapels and on street corners, speaking to coal miners, factory hands, and the destitute that more polished clergy often ignored. His sermons were marked by plain language and fiery conviction. Booth didn’t believe in a sanitized gospel for the drawing room; his was a gospel meant for the gutters, the factories, and the slums.

His ministerial career, though sincere, was restless. Booth grew increasingly frustrated with the institutionalism of the Methodist hierarchy. He wanted to reach the unreached, and bureaucracy got in the way. Eventually, he left the formal Methodist ministry and became an itinerant evangelist. Alongside his wife Catherine, a formidable preacher in her own right, Booth launched what was originally called “The Christian Mission” in London’s East End in 1865.

The organization’s modest beginnings included a tent, some folding chairs, and a message of hope, but Booth had a vision. In 1878, after a colleague commented that they were like “an army of volunteers,” another member replied, “Volunteer? I’m a regular!” The phrase stuck, and soon Booth renamed the ministry the Salvation Army. The new name reflected the group’s disciplined, militaristic structure which included officers, uniforms, and a clear chain of command. They were waging war against poverty, sin, and despair.

Booth understood something many of his contemporaries did not: that the conditions of the body could be just as pressing as the condition of the soul. Salvation, in Booth’s mind, required both. His organization pioneered a holistic form of ministry. Alongside street preaching and open-air revivals, the Salvation Army established soup kitchens, lodging houses, job training programs, and rescue homes for women trapped in prostitution. In an era when charitable work often served as a pretext for social control or religious coercion, Booth’s efforts stood out for their earnestness and compassion.

Not everyone approved. The Army’s emphasis on temperance drew the ire of pub owners and brewers. In some towns, Salvationists were attacked in the streets. Even within the church, there was skepticism. Some bristled at the Salvation Army’s militaristic tone. Others, more scandalously, objected to Booth’s policy of allowing women to preach and hold leadership positions. Catherine Booth, known as the “Army Mother,” had long argued that “if we are to better the future, we must disturb the present.” In this respect, the Booths disturbed plenty.

William Booth’s writings further reveal the breadth of his vision. His 1890 book, In Darkest England and the Way Out, drew a provocative comparison between the slums of England and the uncharted interior of Africa. While many considered “darkest Africa” a metaphor for barbarism, Booth used “darkest England” to indict the spiritual and moral neglect of industrial Britain. In the book, he laid out a comprehensive social plan that included farming colonies, rehabilitation centers, and employment bureaus. It was both a critique and a call to action, and it sold over 100,000 copies in its first year.

Beyond In Darkest England and the Way Out, William Booth was a prolific writer whose works deeply influenced Christian social reform. His sermons, pamphlets, and articles emphasized the urgent need for practical Christianity that addressed both spiritual salvation and social justice. Booth’s writings often tackled issues like poverty, temperance, and the role of women in the church, consistently arguing for an active faith that engaged the marginalized. Through publications like The War Cry, the Salvation Army’s official newspaper, Booth communicated his vision widely, inspiring supporters and challenging complacency. His literary legacy helped shape modern evangelical social activism.

As the Salvation Army grew, so did its global reach. By the early 20th century, the movement had spread to dozens of countries across six continents. Booth traveled widely, often in poor health, to encourage the work abroad. Despite failing eyesight and increasing fatigue, he remained committed to the Army’s mission until the end of his life.

When William Booth died in 1912, over 40,000 people passed by his coffin during public viewings. His funeral at London’s Olympia Hall drew thousands more, including Queen Mary and representatives from across the British Empire.

Booth’s contribution was in reimagining what Christian faith could look like in a modern industrial society. He believed that the gospel had something to say not only about heaven, but also about housing, hunger, and human dignity. For Booth, “soup, soap, and salvation” were one mission. Perhaps that is why his legacy endures. The Salvation Army rapidly expanded beyond England to become a global movement, reaching over 130 countries today. Its international mission focused on serving the poor, homeless, and marginalized, combining evangelism with practical aid such as disaster relief, shelters, and rehabilitation programs. The organization’s structured, military-style approach helped it adapt efficiently across diverse cultures while maintaining a unified purpose. From its early work in Europe and North America, the Salvation Army now operates in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Oceania. This global reach reflects William Booth’s vision of a worldwide Christian mission dedicated to social justice and spiritual salvation.

The Salvation Army remains one of the largest social service organizations in the world. Its red kettles, thrift stores, and emergency shelters continue to serve millions each year, regardless of faith background. But even more enduring is the example of its founder who was a man who saw the spiritual in the practical and believed that Christian love, when lived out boldly, could change the world.