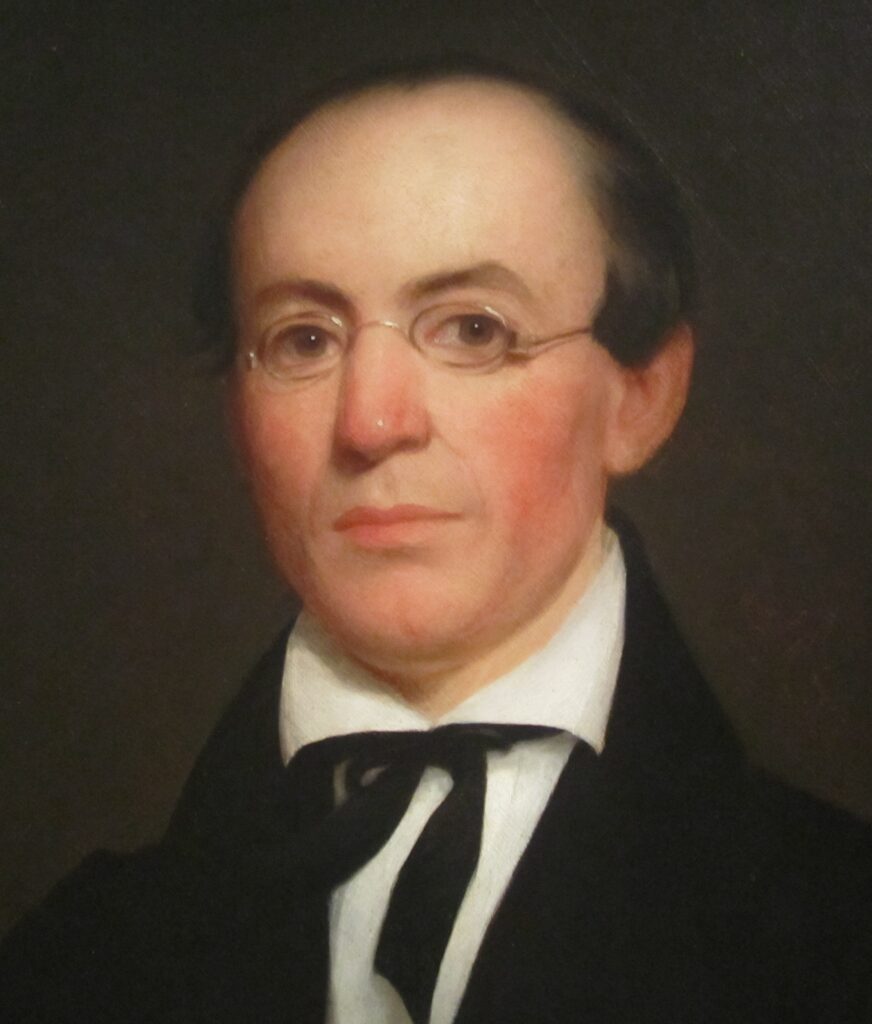

William Lloyd Garrison

December 10, 1805 - May 24, 1879

Abolitionist and Journalist

Abolitionist and Journalist

From Newburyport, Massachusetts

Served in Boston, Massachusetts

Affiliation: Nondenominational

"I am for a religion which emancipates man from all bondage, both within and without. I am for a religion which holds to the sanctity of marriage throughout the world. I am for giving the Bible to every human being on the face of the earth, to be made use of as far as possible, to promote his own highest and everlasting interests. I am for a church which has no stain of blood upon its garments. I am for a Christ whose every testimony is to the value of man to a child of God, and whose mission it is to destroy all the works of the devil, to emancipate those who are in bondage, and to set every captive free. I understand this to be the religion of the Anti-Slavery enterprise, and the religion of this Convention ; but a religion unfashionable, proscribed and outlawed even to this day, while that which is falsely called the Christian religion bears sway every where, and the consequence of that sway is the enslavement of every seventh person in our land, to be owned, and bought, and sold, and treated as a beast of burden! Let that religion be accursed, and the religion of freedom prevail!"

William Lloyd Garrison, born in 1805 in the seaside town of Newburyport, Massachusetts, came of age in a nation teetering between the ideals of liberty and the brutal realities of human bondage. The son of a struggling Baptist mother and an absent father, Garrison was raised in poverty and piety. His mother, Frances Maria Garrison, infused in him a deep moral seriousness and a reverence for the Christian faith that would shape the arc of his life. Though he had little formal education, he entered the world of ideas through the printing press. By age thirteen, apprenticed at the Newburyport Herald, he was learning not only to set type but to wield words with precision and purpose.

In his twenties, Garrison embraced the cause of abolition with unflinching devotion. His early experiences with hunger, hardship, and his mother’s fervent faith merged into a singular moral clarity: that slavery was the sin of the American republic. He began publishing fiery denunciations of the institution, first in The Genius of Universal Emancipation under the mentorship of Quaker abolitionist Benjamin Lundy, and soon in his own journal, The Liberator, founded in 1831. In the inaugural issue, Garrison declared, “I am in earnest—I will not equivocate—I will not excuse—I will not retreat a single inch—and I will be heard.” These were not the words of a political strategist. They were the words of a prophet.

At the heart of Garrison’s abolitionism was an unwavering Christian faith. Converted during the fervor of the Second Great Awakening, he was drawn not to denominational loyalty, but to the gospel’s radical demands for justice, mercy, and truth. Garrison read the Bible as a call to action. Slavery, to him, was a spiritual abomination. To tolerate it was to be complicit in sin.

From early on, Garrison made clear that his abolitionism was inseparable from his theology. He viewed slavery as a blight on the Christian conscience of the nation. His brand of evangelical Christianity was intensely moral and individualistic: each person, he believed, had a sacred duty to resist evil. The Christian gospel, in his view, demanded immediate emancipation. Gradualism was, for Garrison, a moral evasion. The very souls of both the enslaved and their enslavers were at stake.

But Garrison’s religious convictions also placed him at odds with many mainstream churches. He grew increasingly critical of what he called “pro-slavery Christianity,” the churches and denominations that either supported slavery outright or remained shamefully silent. He accused them of betraying Christ himself. “A religion that upholds slavery,” he thundered, “is not the religion of Jesus Christ.” This growing antagonism led Garrison to reject organized religion as it existed in America. In 1833, he helped found the American Anti-Slavery Society, and in the years that followed, he called for what he saw as a purer, more Christlike Christianity that aligned with the Sermon on the Mount, not with slave codes and property rights.

By the mid-1830s, Garrison was more than an editor; he was the moral conscience of a movement. His rhetoric was uncompromising. He burned copies of the Constitution, calling it “a covenant with death and an agreement with hell” for its protections of slavery. His insistence on immediate emancipation alienated moderates and politicians, yet it galvanized a new generation of reformers, especially in the North. His critics saw him as extreme, even dangerous. But Garrison saw himself as a servant of divine justice.

Through The Liberator, Garrison gave voice to countless abolitionists, black and white, men and women, while insisting on nonviolence and moral suasion as the means of reform. He championed the writings of black leaders like Frederick Douglass, whose own narrative bore witness to the horror of slavery and the power of freedom. Although Garrison and Douglass would later part ways over tactics and strategy, Garrison remained steadfast in his belief that Christianity demanded absolute commitment to the abolition of slavery.

His 1860 pamphlet, “The ‘Infidelity’ of Abolitionism,” addressed accusations that abolitionists were irreligious. Garrison responded by aligning the movement with the legacy of biblical prophets and reformers. Far from being hostile to faith, abolitionists, he argued, were its truest inheritors. “True Christianity,” he wrote, “is always on the side of the oppressed.” He insisted that those who fought slavery were acting in obedience to the highest commands of Scripture, not in defiance of them.

Garrison’s spiritual language was integral. His understanding of God was grounded in righteousness and justice. He spoke often of a divine law higher than any constitution or statute. And his activism extended beyond slavery. He advocated for women’s rights, temperance, and pacifism, believing that all injustice was interconnected. His commitment to nonresistance, a stance that rejected violence in all forms, was grounded in the teachings of Jesus and the ethical demands of the gospel.

After the Emancipation Proclamation and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, Garrison felt his life’s work was largely complete. He retired The Liberator in 1865, but his voice remained a powerful one in public life. He turned his attention to Reconstruction, urging the federal government to secure rights for freed people, and continued advocating for social reform until his death in 1879.

While the details of Garrison’s personal church attendance remain unclear, what is certain is the depth of his public faith. He may have distanced himself from organized religion, particularly as many churches remained complicit in slavery, but his spiritual convictions were anything but private. Garrison lived his theology in the public square, preaching a gospel of justice through every editorial, speech, and petition. If he did not sit regularly in a pew, it was not for lack of devotion but because he saw the world itself as his congregation and the abolitionist cause as his sacred calling. William Lloyd Garrison’s legacy endures not simply because he denounced slavery, but because he did so with a voice that echoed the ancient prophets. His religion was not the quiet piety of Sunday sermons, but a fervent, active faith rooted in justice. For Garrison, Christianity without action was hypocrisy. He lived by a gospel that demanded sacrifice, courage, and truth-telling.

For further reading:

1. Mayer, Henry. All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1998.

2. Scott, John R., ed. William Lloyd Garrison at Two Hundred. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

3. Sinha, Manisha. The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016.